This repository has been archived by the owner on Apr 16, 2020. It is now read-only.

-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 11

Commit

This commit does not belong to any branch on this repository, and may belong to a fork outside of the repository.

- Loading branch information

Showing

7 changed files

with

327 additions

and

3 deletions.

There are no files selected for viewing

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

File renamed without changes.

File renamed without changes.

This file contains bidirectional Unicode text that may be interpreted or compiled differently than what appears below. To review, open the file in an editor that reveals hidden Unicode characters.

Learn more about bidirectional Unicode characters

| Original file line number | Diff line number | Diff line change |

|---|---|---|

| @@ -0,0 +1,202 @@ | ||

| # Decentralized Publishing | ||

|

|

||

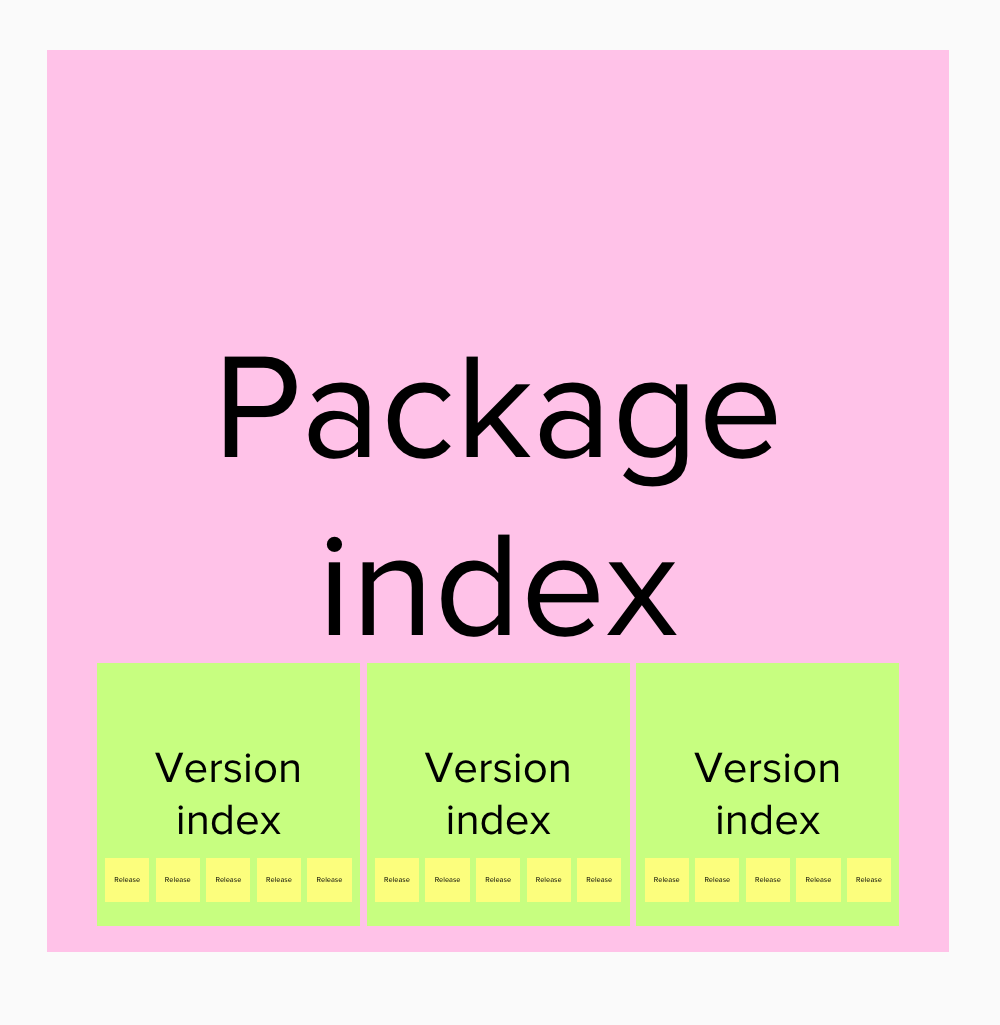

| I started thinking about what the parts of a fully decentralized package manager would look like, ignoring to a certain extent what the actual technology doing the work would be, as a follow up from https://github.com/ipfs/package-managers/issues/50. | ||

|

|

||

| In the majority of issues we've discussed mirroring and supporting existing package manager registries that generally take the form of a centralized authority managing publishing to a particular index. | ||

|

|

||

| _The exception being [Registry-less](https://github.com/ipfs/package-managers/blob/master/categories.md#registry-less) package managers like Go, Swift, Carthage, Deno etc that use DNS as the centralized authority and package/release identifiers are URLs, sometimes with shorthands for GitHub urls._ | ||

|

|

||

| Some terminology: | ||

|

|

||

| **Release:** The actual artifact of software being published as source code and/or binary, usually delivered as a compressed archive (tar, zip etc), they may contain some metadata about the contents but do not know their own CID within a content addressable system like IPFS. | ||

|

|

||

| **Version index:**: Data for a collection of one or more of releases of a particular software project, including the human readable name/number of each release, the content address of the release and usually some integrity data to confirm the content at that address matches what was expected, with IPFS that comes for free. It may also contain some information about the state of each release (deprecated, insecure etc). | ||

|

|

||

| **Version index owner:** A record of one or more identities that can do one or more of the following to a version index: | ||

| - add a new release | ||

| - update an existing release | ||

| - remove an existing release | ||

|

|

||

| In a content addressable world, they are actually publishing a new version of a version index. | ||

|

|

||

| **Package index:** Data for a collection of one or more Version Indexes, including the human readable name for each version index and it's content address. | ||

|

|

||

| **Package index owner:** A record of one or more identities that can do one or more of the following to a package index: | ||

| - add a new version index to package index | ||

| - update an existing version index | ||

| - remove an existing version index | ||

|

|

||

| In a content addressable world, they are actually publishing a new version of a Package index when making one of those changes. | ||

|

|

||

|  | ||

|

|

||

| ## Identity | ||

|

|

||

| Identity and permissions around changing indexes depending on the [category](https://github.com/ipfs/package-managers/blob/master/categories.md#implementation-categories) of package manager. | ||

|

|

||

| For example: | ||

|

|

||

| **File system based:** These usually store releases, version indexes and package indexes all within the same root filesystem, meaning that the administrators of that system usually have permission to update all indexes, those administrators also the ability to make more administrators but must trust them with all indexes. | ||

|

|

||

| **Git based:** These usually store releases, version indexes and package indexes all within the same git repository, meaning that the administrators of that repository usually have permission to update all indexes, those administrators also the ability to make more administrators but must trust them with all indexes. | ||

|

|

||

| **Database based:** These tend to have more fine grained permissions, identities can be given limited access to only certain version indexes, and only the ability to update information about those version indexes in the package indexes. Those identities often have the ability to manage access to those version indexes by other identities as well. Access can also be limited to certain actions like disabling deleting data from indexes. Administrators of the database have access to all indexes. | ||

|

|

||

| **Registry-less:** The permission setup can vary with url based setups, administrators who control the DNS for a domain will have the ultimate ability to change the data available from urls on that domain, although usually the web server that the DNS record resolves to takes care of permission setups, any administrator of that web server usually also has access to change the data for that domain. | ||

|

|

||

| One difference with registry-less systems is that there is usually no single administrator that has control DNS of all domains involved (ignoring top level DNS authorities like ICANN), although within a private network, a network administrator can override certain levels of DNS configuration but other security features like TLS may limit functionality in that case. | ||

|

|

||

| In a decentralized package manager, identity and access controls require a different approach due to the lack of an administrator that has access over the whole system. | ||

|

|

||

| Rather than there being just one version index for a project with a unique, human readable name, there can be instead any number of instances of a version index for a project, each one owned by an identity which factors into the globally unique name for that version index. | ||

|

|

||

| Because there is no central naming authority, any identity has the ability to publish a new release of a project and update their own copy of a version index to include that release. | ||

|

|

||

| For example, below are two different version indexes created by two different identities, which share the first two releases: | ||

|

|

||

| ```json | ||

| { | ||

| "owner_identity": "dave:4ba0d198425a112c335a112c334e92848d76905e69a60de3f57e", | ||

| "version_index_name": "libfoo", | ||

| "releases": [ | ||

| { | ||

| "number": "1.0.1", | ||

| "cid": "Qm2453256c...510b2" | ||

| }, | ||

| { | ||

| "number": "1.0.2", | ||

| "cid": "Qm3f53392...4f877" | ||

| } | ||

| ] | ||

| } | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| ```json | ||

| { | ||

| "owner_identity": "lucy:dc99e9aa86fab83a062cff5e0808391757071a3d5dbb942802d5", | ||

| "version_index_name": "libfoo", | ||

| "releases": [ | ||

| { | ||

| "number": "1.0.1", | ||

| "cid": "Qm2453256c...510b2" | ||

| }, | ||

| { | ||

| "number": "1.0.2", | ||

| "cid": "Qm3f53392...4f877" | ||

| }, | ||

| { | ||

| "number": "1.0.3", | ||

| "cid": "Qm20d2ca...b41a4" | ||

| } | ||

| ] | ||

| } | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| Those indexes are effectively named `%{owner_identity}:%{version_index_name}`, for example `lucy:dc99e9aa86fab83a062cff5e0808391757071a3d5dbb942802d5:libfoo`, but these names are not very meaningful or memorable to humans. | ||

|

|

||

| _Note: I'm skimming over content addressability and versioning of version indexes for simplicity here_ | ||

|

|

||

| Package indexes also have a similar naming approach, where the owner has curated a number of version indexes together. Again any identity has the ability to publish a new package index, for example, two similar package indexes with libfoo from different version indexes: | ||

|

|

||

| ```json | ||

| { | ||

| "owner_identity": "molly:f6f7e983afc59354c91673d637c22072ec68f710794f899ae747", | ||

| "package_index_name": "lib_node_modules", | ||

| "version_indexes": { | ||

| "libfoo": "lucy:dc99e9aa86fab83a062cff5e0808391757071a3d5dbb942802d5:libfoo", | ||

| "libbar": "fred:d0cfc2e5319b82cdc71a33873e826c93d7ee11363f8ac91c4fa3:libbar", | ||

| "libbaz": "anna:55579b557896d0ce1764c47fed644f9b35f58bad620674af23f3:libbaz" | ||

| } | ||

| } | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| ```json | ||

| { | ||

| "owner_identity": "andrew:d979885447a413abb6d606a5d0f45c3b7809e6fde2c83f0df", | ||

| "package_index_name": "lib_node_modules", | ||

| "version_indexes": { | ||

| "libfoo": "dave:4ba0d198425a112c335a112c334e92848d76905e69a60de3f57e:libfoo", | ||

| "libbar": "fred:d0cfc2e5319b82cdc71a33873e826c93d7ee11363f8ac91c4fa3:libbar", | ||

| "libbaz": "anna:55579b557896d0ce1764c47fed644f9b35f58bad620674af23f3:libbaz" | ||

| } | ||

| } | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| Note here how a package index can provide human-meaningful names to version indexes that it includes. The standalone version index `"dave:4ba0d1...3f57e:libfoo"` is mapped to a short readable name `libfoo`, much in the same way that a version index provides a mapping between the content address of a release and it's human-meaningful number, `"dave:4ba0d1...3f57e:libfoo"` maps the content address `Qm3f53392...4f877` to the number `1.0.2`. | ||

|

|

||

| This is same mapping happens in centralized registries but it is usually implicit rather than explicit, the npm module `react` by default a shorthand for https://registry.npmjs.org/react, but an end user may choose to override that default and point to a private registry instead for their project: `https://internal-npm-registry.enterprise.com/react`. | ||

|

|

||

| ## Dependencies | ||

|

|

||

| When a software project declares a dependency on another software project via it's package manager configuration, the usual practice to specify the short human-meaningful name and an acceptable range of releases that it should work with. | ||

|

|

||

| Because a release can be included in many version indexes and package indexes, the release itself usually declares it's dependency requirements in a index agnostic approach. For example, rather than specifying the full URL (`https://registry.npmjs.org/react`) of a dependency, a short name or alias is used `react`, this allows different registries to host the same packages without needing to rewrite the metadata for every package with their specific registry details. | ||

|

|

||

| This is key for decentralized package managers as the package index name (`andrew:d979885447a413abb6d606a5d0f45c3b7809e6fde2c83f0df:lib_node_modules`) is much less human-meaningful than a centralized registry url. | ||

|

|

||

| Acceptable version numbers in dependency requires have similar properties, when declaring a range of acceptable versions, the author is encouraged to be as broad as possible in acceptable version ranges so as to reduce the likelihood of conflicts with other packages requirements of that same dependency during resolution. | ||

|

|

||

| Unlike package names, version number requirements for dependencies may also attempt to take into account future releases that are likely to work with that release, for example using [semantic versioning](https://semver.org/) to allow for minor patch releases whilst avoiding major breaking change releases. | ||

|

|

||

| From a decentralized package manager's point of view the key attribute of dependency requirements are that they are agnostic to the exact name of the version and package indexes used, instead preferring the local names (`react`) and number ranges (`>= 1.0.0`) which are defined within the indexes that the end user chooses to use. | ||

|

|

||

| ## Discovery | ||

|

|

||

| One of the more challenging problems with decentralized package management is that of discovery, finding information about packages in a network. There are three main categories of discovery: | ||

|

|

||

| ### Search | ||

|

|

||

| Search is the initial starting point of finding an open source package that solves a problem for you, for example "a library to parse xml documents in javascript". This usually involves searching for keyword matches across names, descriptions, tags and other textual metadata, with the aim of finding and comparing details of various matches, resulting in the address of one or more version indexes. | ||

|

|

||

| In centralized registries, relevant data from the package index is often replicated to a separate, specialized full-text-search index. More general web search engines like Google also index the contents of individual html package pages. | ||

|

|

||

| In a decentralized environment there won't be an automatic index created of every package published, services may need to be built to help index the variety of new indexes and packages being published, things like: | ||

|

|

||

| - opt-in announcement of releases and index updates to indexing services | ||

| - trawling existing known indexes and source code to discover package/version indexes and releases | ||

| - peer-to-peer sharing of package/version indexes and releases where connected users also keep track of their peers published package data | ||

|

|

||

| ### Resolution | ||

|

|

||

| Once you have a package that you wish to install, say [`react`](https://www.npmjs.com/package/react), there is are two further stages of discovery that happen before the installation is complete: | ||

|

|

||

| 1. A version index needs to be discovered for that package which provides list of available releases, of which one will be chosen to be installed that doesn't conflict with other existing package requirements usually the newest or highest number. | ||

|

|

||

| 2. A specific release many declare a number of dependencies by name, [`[email protected]`](https://unpkg.com/[email protected]/package.json) has four dependencies with version range requirements: | ||

|

|

||

| ```json | ||

| "dependencies": { | ||

| "loose-envify": "^1.1.0", | ||

| "object-assign": "^4.1.1", | ||

| "prop-types": "^15.6.2", | ||

| "scheduler": "^0.13.6" | ||

| }, | ||

| ``` | ||

|

|

||

| For each one of those dependencies the same two discovery steps need to be performed until the full dependency tree has been resolved. | ||

|

|

||

| In a centralized registry this stage of discovery usually involves looking up existing version indexes within the same database, some even have specialized APIs to query the indexes in bulk because the data is all stored in the same place. | ||

|

|

||

| This process can also fail in two ways: | ||

|

|

||

| 1. If you cannot find a version index to match the package name you are searching for, the classic example is [`left-pad`](https://www.theregister.co.uk/2016/03/23/npm_left_pad_chaos/) where a popular package's version index was removed from the central registry completely and many users couldn't successfully install that package. | ||

|

|

||

| 2. If you cannot find a release number within a version index that satisfies all of the dependency requirements for that package that other packages with depend on it have specified. This may be because an existing release has been removed, or because one of the dependency requirements specifies a release number that conflicts with other dependency requirements within the same tree. | ||

|

|

||

| One way that decentralized publishing can help minimize these kinds of discovery problems is via validation on or before the publishing of indexes, ensuring that there are no unreachable parts of a dependency tree within an index, and then automatically advising on how to find and correct those errors if they are caught. | ||

|

|

||

| ### Updates | ||

|

|

||

| Existing software packages often have multiple releases published as bugs are found and fixed or functionality improvements added. When these new releases are published, end users of the package need a way of finding out that those new versions are available. | ||

|

|

||

| This usually is done by adding the new release to existing version indexes, there are also services that can announce new updates via email, rss, push notifications or even as a direct request to update that dependency requirement within a codebase such as [Dependabot](https://dependabot.com/). | ||

|

|

||

| There may also be updates to be discovered about existing releases, such as a state change ("This release has been marked as deprecated") or a security vulnerability or legal notice has been published about it, although the contents of the release is not expected to change, the metadata about it within a version index may be updated to reflect the change. | ||

|

|

||

| Whilst centralized registries make it very easy to have update information available to all users, it also makes it harder for end users to opt-out of getting that update information which can have a negative impact on the reproducibility of a projects dependency tree, either due to data being removed or new data being added that changes the results of dependency resolution in an undesirable manner. | ||

|

|

||

| ## Tooling | ||

|

|

||

| When it comes to decentralized publishing, and consuming those decentralized indexes, new tooling will need to be built to help encourage the use of standards and compatibility between indexes as well as extra services for aiding in some of the discovery problems that arise. Experimenting and finding out what those tools might look like would be a useful task to think about before starting to implement decentralized publishing. | ||

|

|

||

| One other aspect that I've yet to explore is the idea that version and package index "owners" don't need to be humans, but could instead be software that does the heavy lifting of publishing and curating indexes together. This could open the door to multiple levels of identities of ownership and connection between different indexes, perhaps even federations of indexes that get combined together by groups or communities of end users. |

File renamed without changes.

Oops, something went wrong.