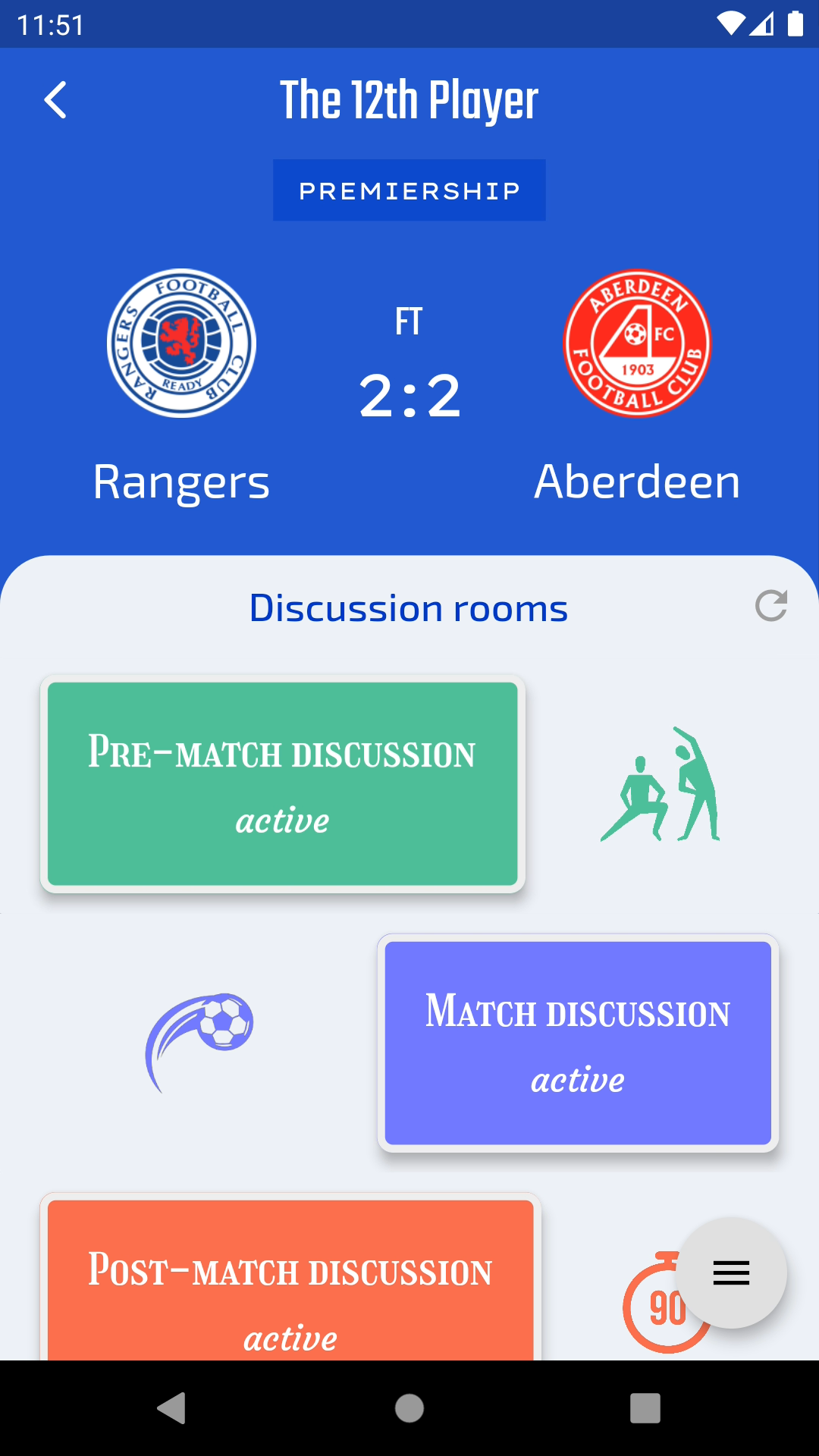

The12thPlayer mobile app written in Flutter. The goal of the application is to bring football fans closer together by providing a friendly, feature-rich platform where they can interact with each other in many different ways. The app does all of the usual football app things like live match events, lineups, and stats, but its main focus is on fans interconnecting with other fellow fans in order to build a strong and united community.

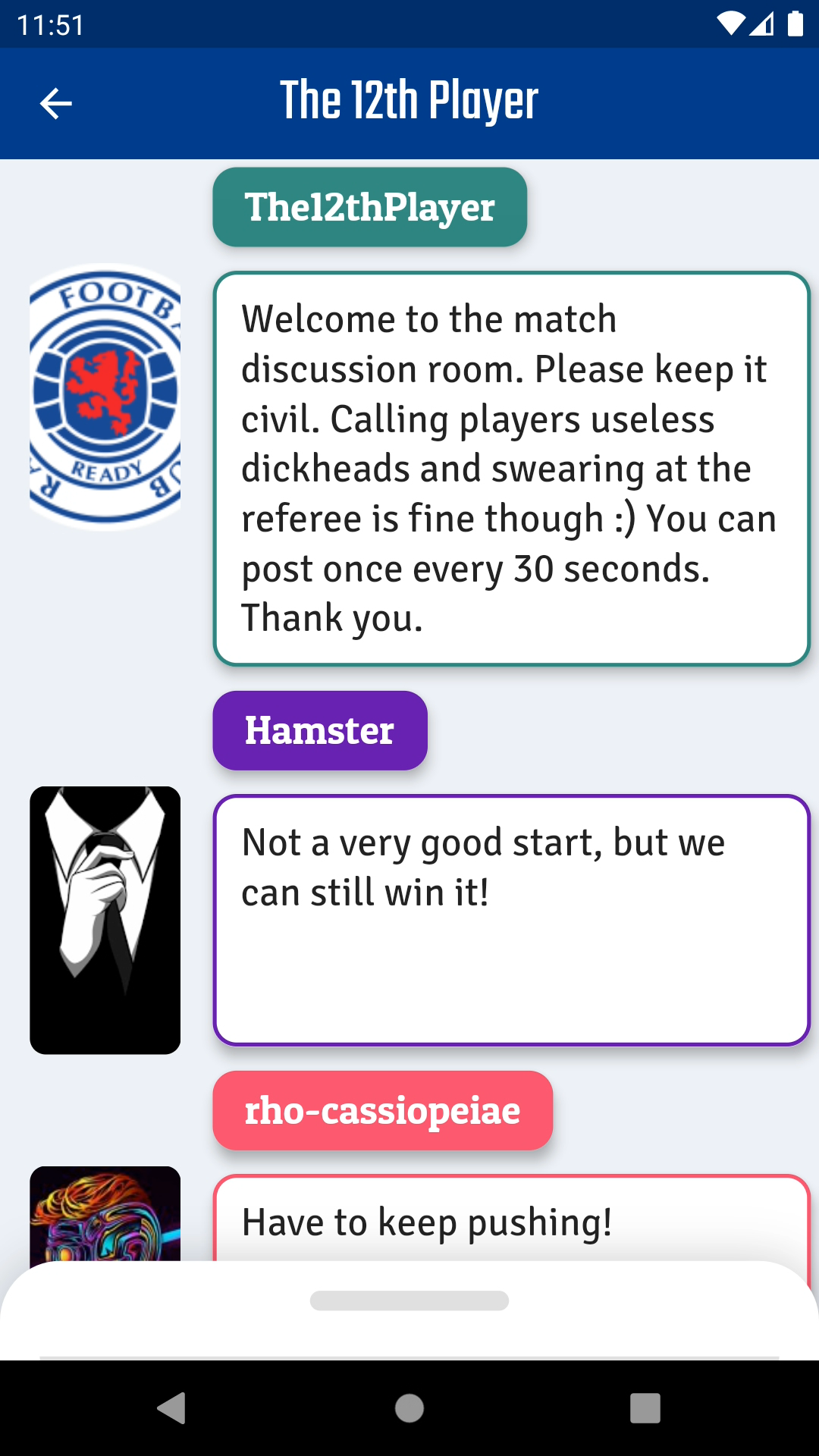

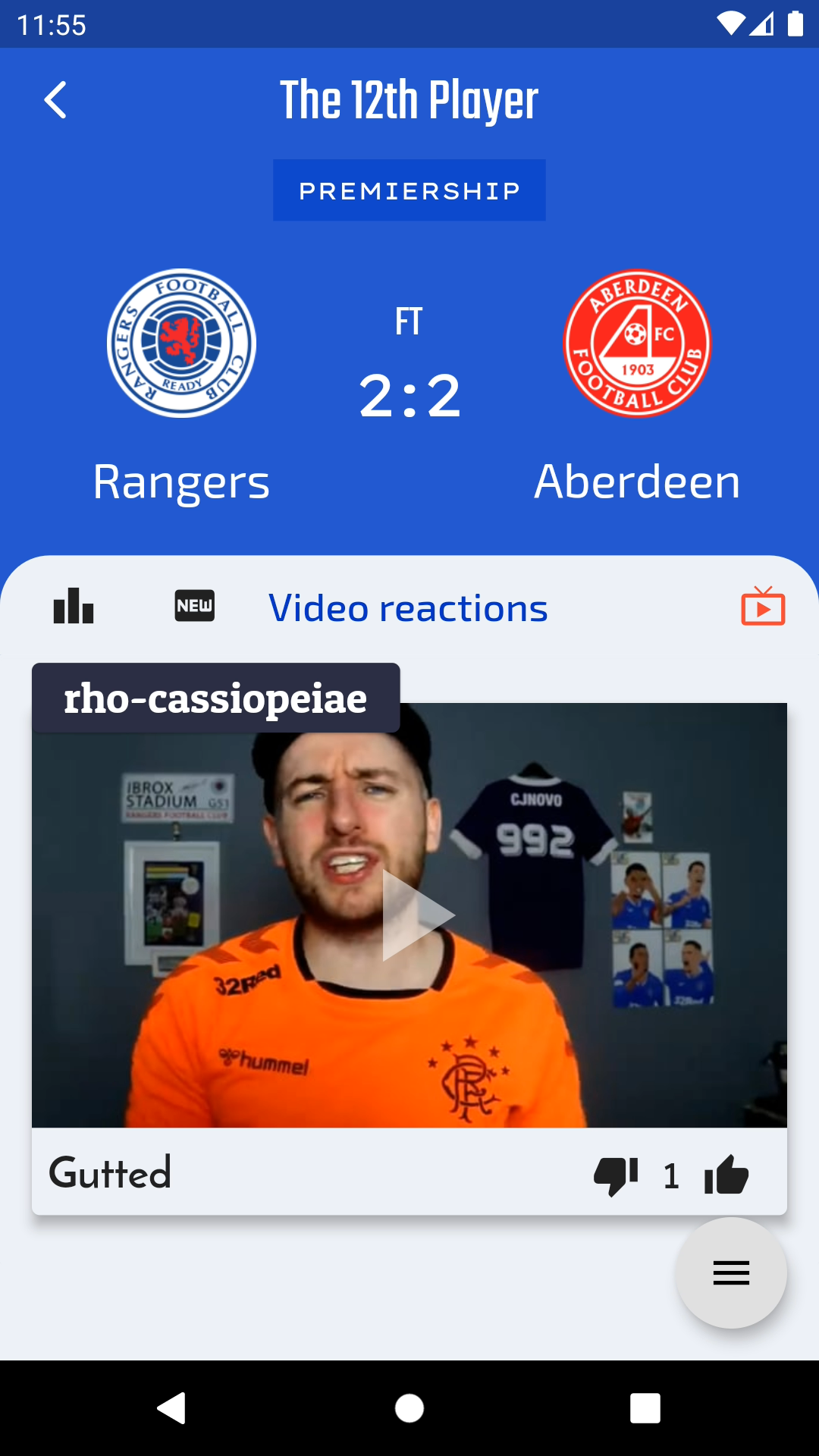

You can chat about a game in a discussion room, watch post-match fan video reactions and post your own, rate players' and managers' performances, predict match outcomes, and more.

For the server side of the application go to this repository.

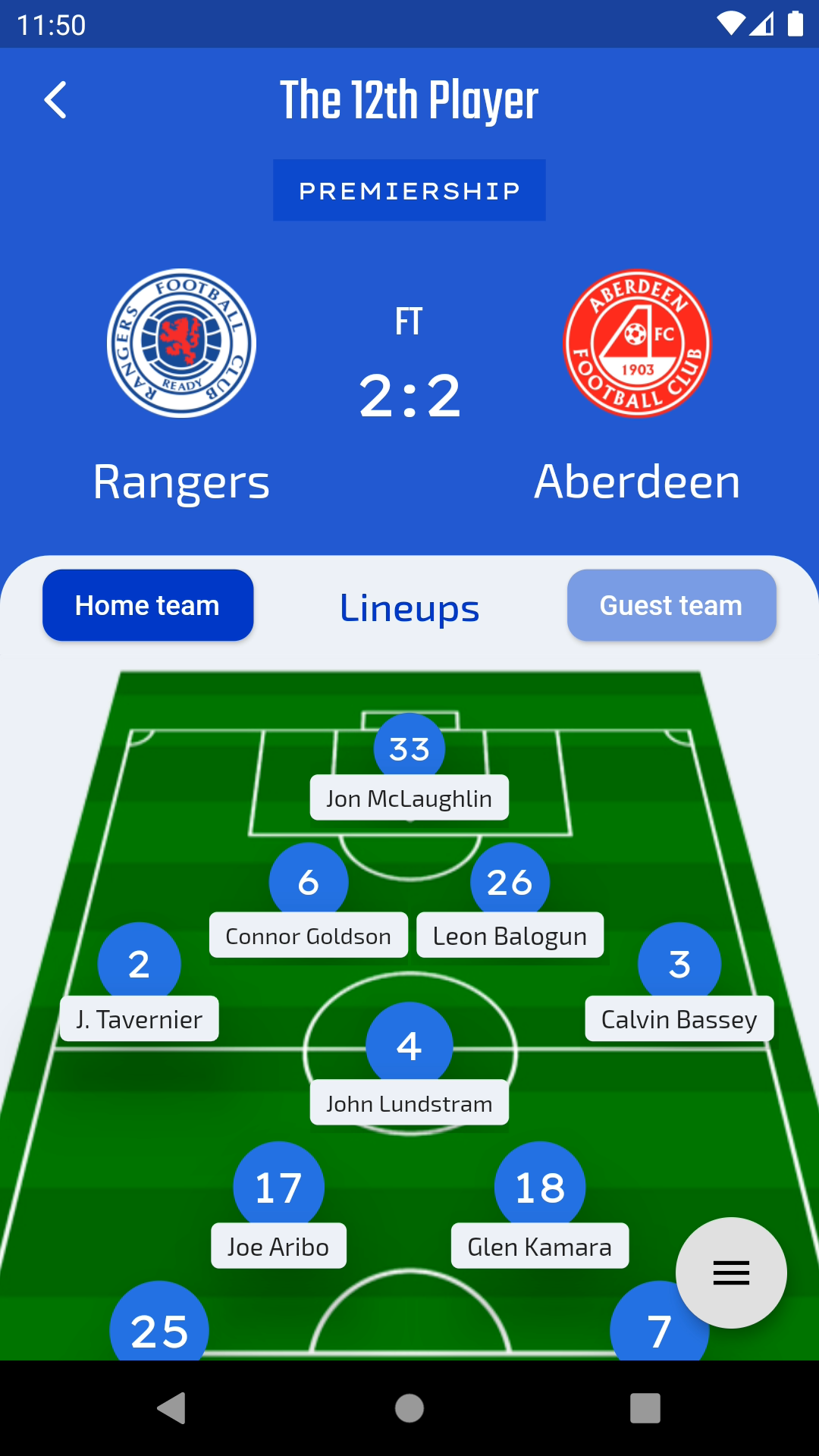

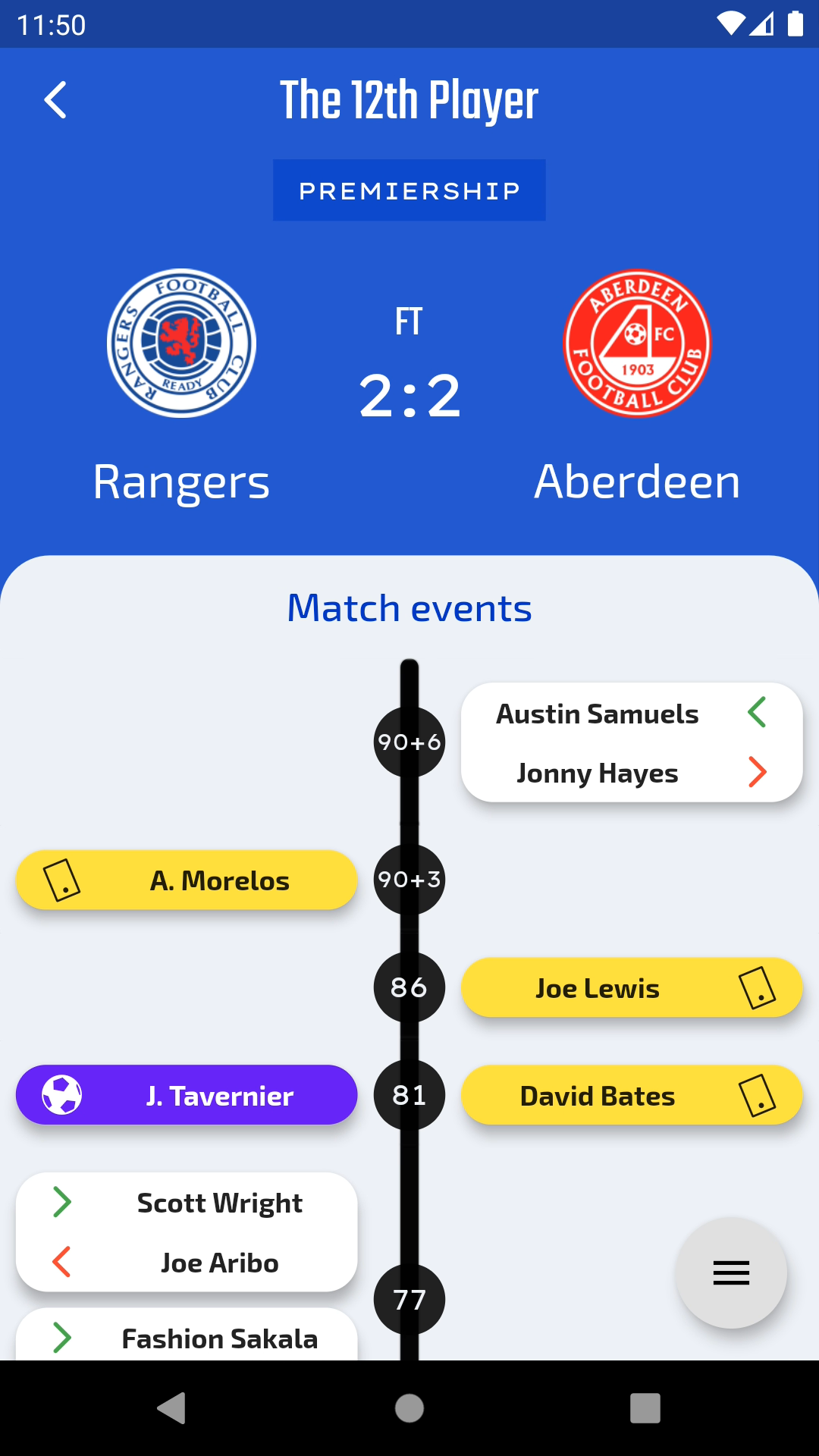

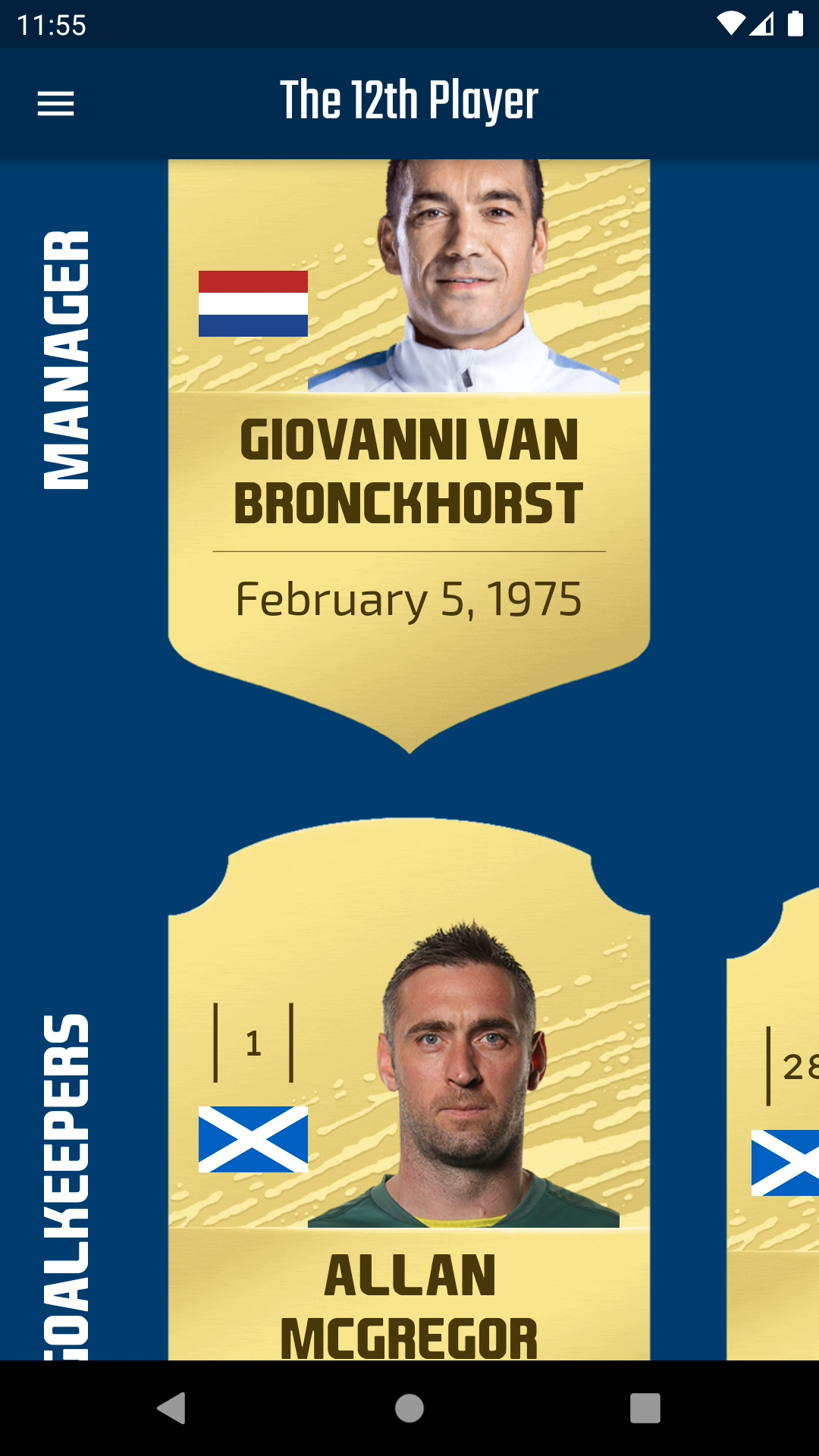

Live match events, lineups, stats.

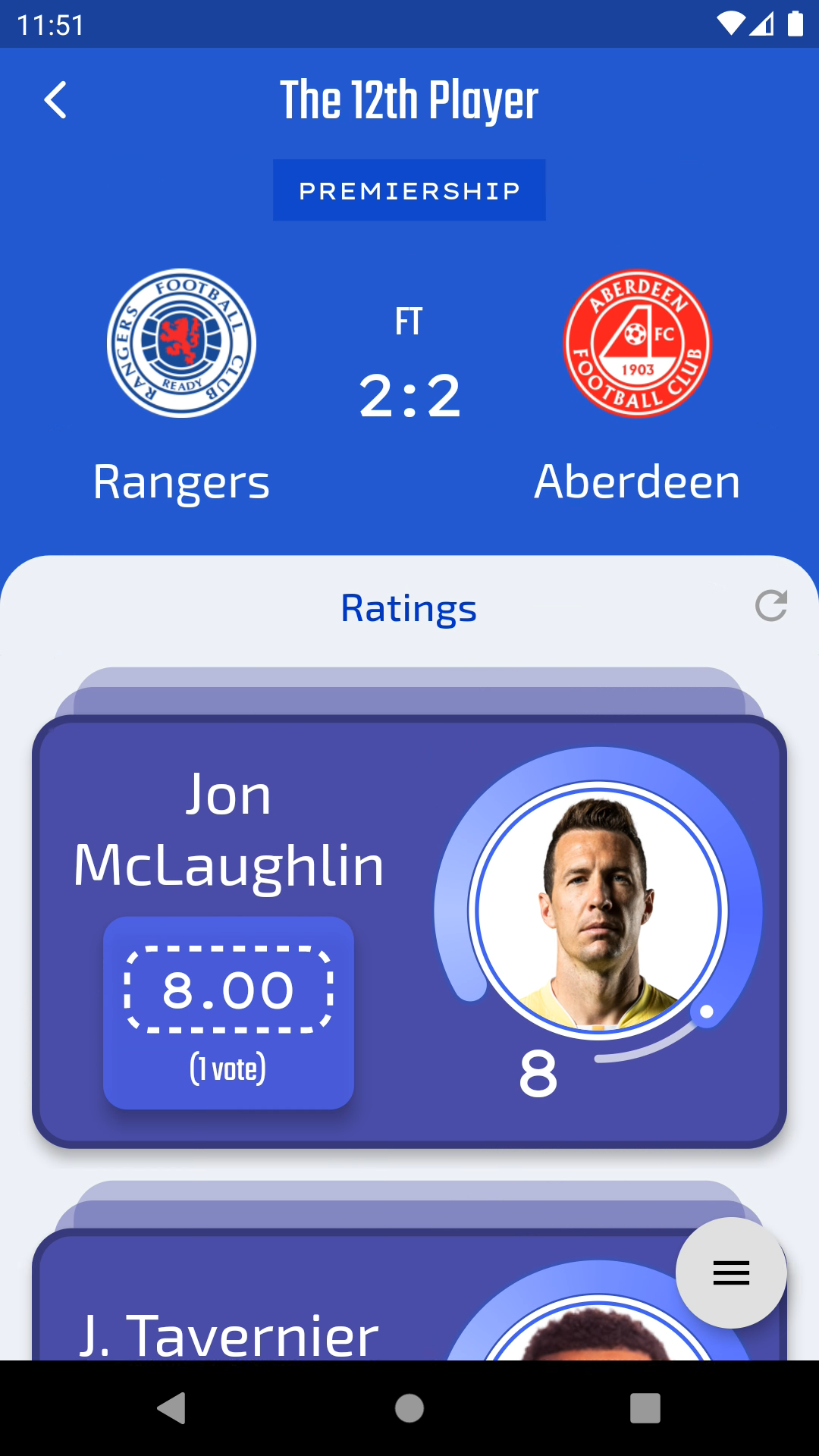

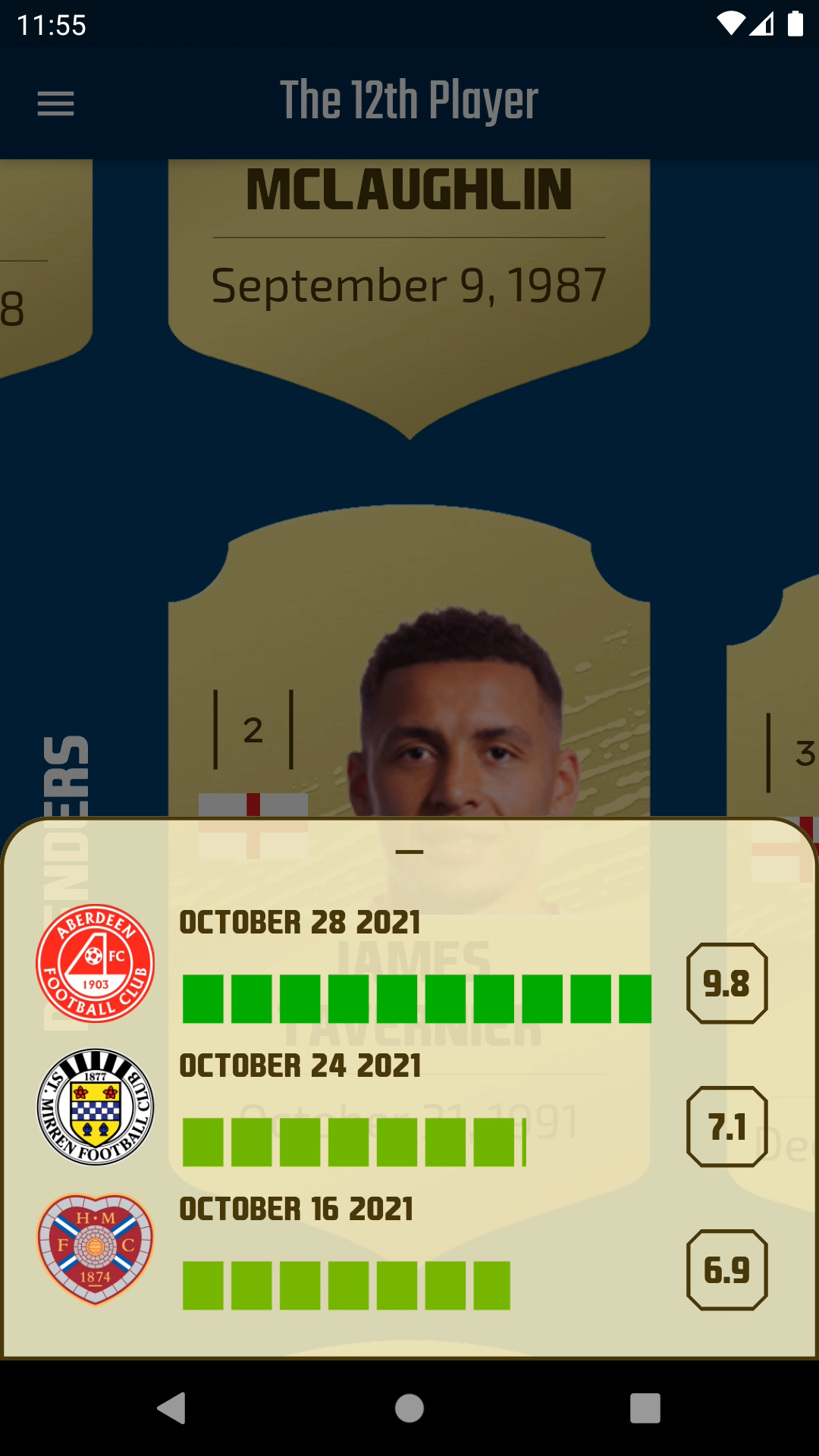

Player ratings. Players' performance history.

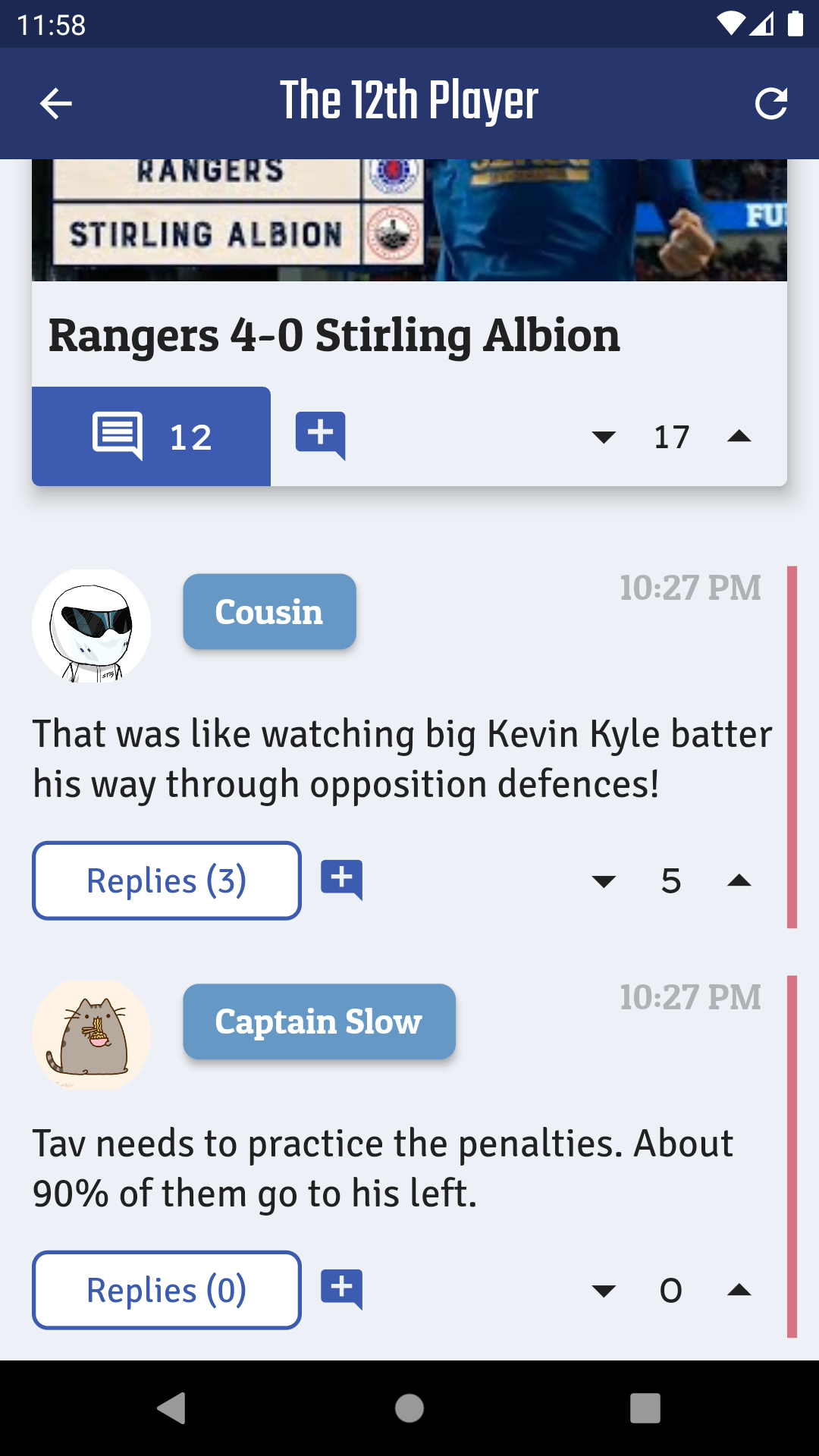

Live match discussions.

Fan video reactions.

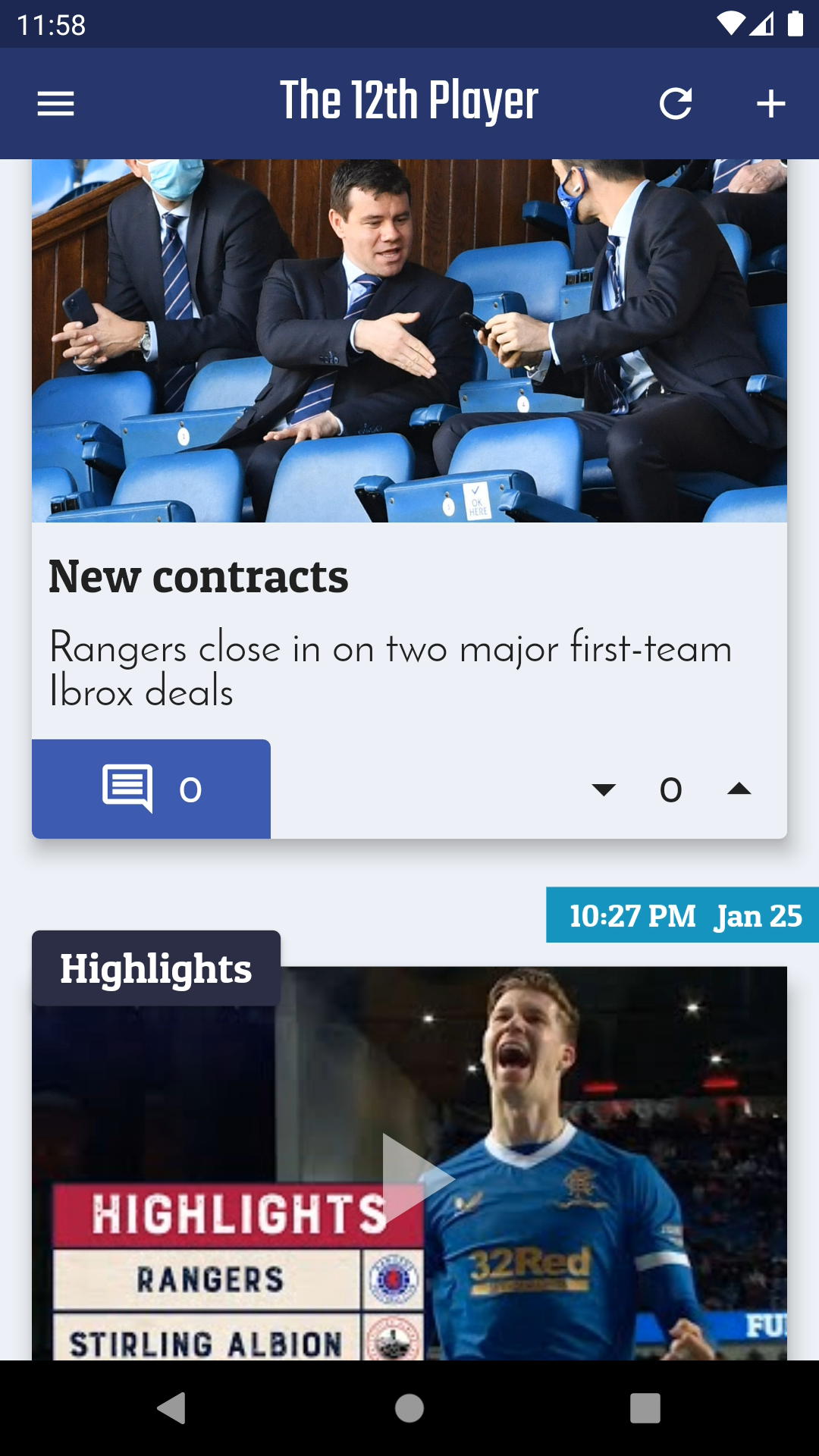

News feed.

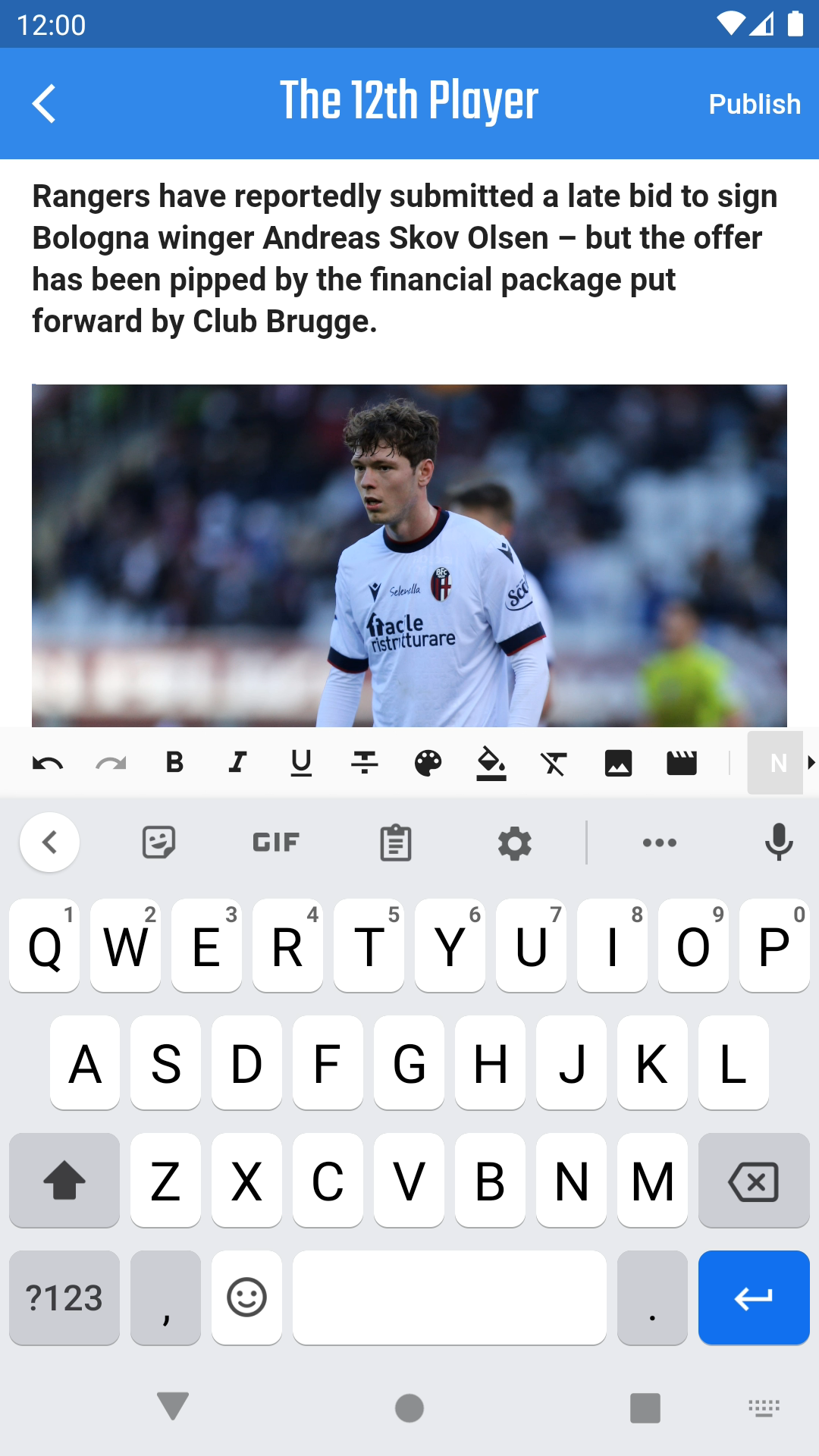

User blogs — In Progress.

Match predictions — In Progress.

User reputation system — In Progress.

Rating players' attributes FIFA-style — Planned.

Forum — Planned.

This Flutter app is in many ways a learning project. Having never used Flutter before, working on the project I've spent a considerable amount of time figuring out how to best organize files, manage state, handle errors, interact with local db, etc. After trying out a lot of popular approaches and packages I decided on the following.

The current king of state management in Flutter is provider package, with riverpod angling to usurp it. I used provider to implement a couple of features of the app in order to test it on something more than just the standard "counter" example, but in the end decided to cut it out. I have several problems with provider, two biggest of which are the way it handles providers depending on other providers (using proxies), which is hella ugly, and the fact that provider actively pollutes widget tree with junk.

Widget tree in Flutter is supposed to be a block-schema representation of the UI that you get on screen. But using provider fills it with widgets which have nothing to do with UI, so you no longer have a one-to-one correspondence between what you have in code and what you actually see. Provider widgets are purely functional widgets, so, in my opinion, do not belong in the UI tree.

I think the main reason the creator of the package opted for this design was because he wanted to make it look native to Flutter and easy to use. After all, this "inherited widget" mechanism is exactly how the built-in cross-cutting concerns widgets are implemented — Navigator, MediaQuery, Theme, etc. But the difference between the built-in and provider widgets is the fact that the former are actually directly related to UI (Navigator controls which page to display, Theme — color and font settings, etc.), so they do belong in the UI tree.

After provider I tried bloc. Bloc is not really a provider's equal alternative. Bloc solves the problem of "how to interact with a service and get state updates", but it doesn't solve the "how to get access to the said service in the first place". Provider solves both. Bloc is a pattern, and there are several bloc packages that implement it. I tested some of them but ultimately decided against using any, since, in my opinion, they don't bring enough value to justify introducing another dependency.

A week-long period of playing aroung with "pure" bloc later I concluded that, yes, I liked it. It's simple, explicit, and encourages to use the well-documented and powerful built-in constructs of Dart and Flutter, such as StreamController, StreamBuilder, async*, etc. However, that is not to say that there aren't any drawbacks.

The most common complaint in regards to bloc is that its concept of "dispatch an event/action and listen on a stream for the result" is quite limiting. What if you want to dispatch an action in a button callback and wait for the result right there in the callback as well? Maybe you want to display a snackbar with the result message or navigate to another page on success. With "pure" bloc it's possible but cumbersome to do — you have to listen a stream for the result, which is not always appropriate. So after some consideration I decided to extend bloc a little.

abstract class CalendarState {} // example base state

mixin AwaitableState<T> { // mixin that you add to action/event classes to make them awaitable

final Completer<T> _stateReady = Completer<T>();

Future<T> get state => _stateReady.future;

void complete(T state) => _stateReady.complete(state);

}

abstract class CalendarAction {} // example base action

abstract class CalendarActionAwaitable<TState extends CalendarState>

extends CalendarAction

with AwaitableState<TState> {} // base class for awaitable actionsIf you want to create an action, dispatching of which results in a response state being returned via stream only, you simply inherit it from CalendarAction. And if you want to create an action, which can have its result state delivered "directly" (await ...) as well as via stream as usual, you inherit it from CalendarActionAwaitable.

class CalendarReady extends CalendarState {

final Calendar calendar;

CalendarReady(this.calendar);

}

class CalendarError extends CalendarState {}

class GetCalendar extends CalendarActionAwaitable<CalendarState> {}Now in the button callback you can do:

var action = GetCalendar();

_calendarBloc.actionSink.add(action);

var state = await action.state;

// do smth with calendarWhen the action is handled you call action.complete(CalendarReady(calendar)) to return the result.

The above code basically allows some calendar actions to "bring their own response transport", which doesn't necessarily have to be future, you can use streams as transport as well.

I've seen people working around this bloc limitation differently — by foregoing the use of input actions for some features and, instead, simply calling public methods on a bloc class. But if you do this you may as well don't use bloc at all, since its main benefit is complete decoupling which is achieved by only accepting input actions and returning output states via streams.

Having solved that, I started looking for a solution for the second problem — how widgets (sitting arbitrarily deep in a widget tree) can get access to bloc instances.

Kiwi package quickly caught my attention. The backend developer in me loves dependency injection pattern and DI containers. Kiwi allows you to write code like this:

class CalendarService {

// provides calendar-related functionality

}

class CalendarBloc {

final CalendarService _calendarService;

final StreamController<CalendarAction> _actionChannel = StreamController<CalendarAction>();

Sink<CalendarAction> get actionSink => _actionChannel.sink;

CalendarBloc(this._calendarService) {

_actionChannel.stream.listen((action) async {

if (action is GetCalendar) {

var calendar = await _calendarService.getCalendar();

action.complete(CalendarReady(calendar));

} // else if ...

})

}

}

class Injector {

void configure() {

var container = KiwiContainer(); // KiwiContainer is a singleton

// register as singletons, can also register as transient

container.registerSingleton((c) => CalendarService());

container.registerSingleton((c) => CalendarBloc(c<CalendarService>()));

}

}

void main() {

Injector().configure();

runApp(/* ... */);

}Then in any widget to get access to the CalendarBloc instance you write:

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

var calendarBloc = KiwiContainer().resolve<CalendarBloc>();

// ...

}Kiwi will take care of creating instances of CalendarService and CalendarBloc, injecting the former into the latter, and managing the instances' lifetimes (singletons in this case).

You can also use kiwi_generator package together with kiwi to avoid manually writing dependency chains (Injector class), which can be quite cumbersome.

This is all well and good but still not entirely user-friendly. Resolving services from kiwi container like this makes dependencies implicit, meaning, the only way to figure out a widget's dependencies is to comb through its methods. It's much better when dependencies are explicitly declared as a class' generic type parameters, in the constructor, or at least as method parameters. Given that we don't actually own StatelessWidget and State classes (they are framework classes), there is a limit to what we can do. After some experimentation I ended up with the following:

TDependency _resolveDependency<TDependency>() => KiwiContainer().resolve<TDependency>();

abstract class StatelessWidgetWith<TDependency> extends StatelessWidget {

const StatelessWidgetWith({Key key}) : super(key: key);

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return buildWith(

context,

_resolveDependency<TDependency>(),

);

}

Widget buildWith(BuildContext context, TDependency service);

}

abstract class StateWith<TWidget extends StatefulWidget, TDependency> extends State<TWidget> {

TDependency _service;

TDependency get service => _service ??= _resolveDependency<TDependency>();

}Given the above extension, when we want to create a stateless widget that has a dependency on CalendarBloc, we write:

class SomeStatelessWidget extends StatelessWidgetWith<CalendarBloc> {

@override

Widget buildWith(BuildContext context, CalendarBloc calendarBloc) {

// use bloc

// do work, return a widget

}

}And for a stateful widget:

class SomeStatefulWidget extends StatefulWidget {

@override

_SomeStatefulWidgetState createState() => _SomeStatefulWidgetState();

}

class _SomeStatefulWidgetState extends StateWith<SomeStatefulWidget, CalendarBloc> {

CalendarBloc get _calendarBloc => service; // or can use 'service' property directly

// Use CalendarBloc in initState, build, etc.

}

Declaring and resolving dependencies like this makes them explicit and also hides the fact that we use kiwi at all (which would allow for an easy migration to an alternative package, if necessary). No longer our code is littered with KiwiContainer().resolve<T>() calls, instead, it gets called from a single place inside resolveDependency.

And, of course, you can create extension classes for widgets with 2 dependencies — StateWith2<TWidget, TDependency1, TDependency2> and StatelessWidgetWith2<TDependency1, TDependency2> — and with 3, 4, and however many you need.

Note that with this approach, if a transient service uses a resource that needs to be disposed of (socket, for example), it should only be injected into stateful widgets, because stateless ones don't have dispose hooks.

Nobody likes writing try-catch everywhere, it fills code with noise that makes it hard to see what part is actual functionality implementation and what is just window dressing. But since errors are an unavoidable part of any code execution, write try-catch we must.

In the .NET world there is a wonderful package called Polly, which is

a .NET resilience and transient-fault-handling library that allows developers to express policies such as Retry, Circuit Breaker, Timeout, Bulkhead Isolation, and Fallback in a fluent and thread-safe manner.

In other words, it takes it upon itself to implement try-catch blocks for lots of different cases and expose them as policies. So instead of, say, writing a try-catch inside a while loop with a counter, you can just use Polly's retry policy. It is a very elegant yet expressive way to handle errors.

There aren't any Dart/Flutter Polly equivalents, as far as I can tell. So I decided to write a very simplified version of my own. Polly is designed to be used on servers, and on servers there are a lot of things that can go wrong. You need many different policies to cover all possible failures, since you want to minimize downtime.

On client side, on the other hand, there aren't many things that can fail (comparatively), and by far the most common thing you do when failure does happen is retry N times.

The source code of my version of "Polly" is in the general/utils/policy.dart file. It's just over one hundred lines long. Here's how it can be used:

var policy = PolicyBuilder()

.on<SomeError>(strategies: [

When(

someCondition, // e.g., (SomeError error) => error.code == 404

repeat: 2,

withInterval: (_) => Duration(milliseconds: 400),

),

When(

otherCondition,

repeat: 3,

withInterval: (attempt) => Duration( // attempt is [0; 2]

milliseconds: 200 * pow(2, attempt),

),

),

])

.on<AuthenticationTokenExpiredError>(strategies: [

When(

any,

repeat: 1,

afterDoing: _accountService.refreshAccessToken,

),

])

.build();

var result = await policy.execute(() async {

// Do work here.

// If throws SomeError, the execution will be repeated according to the strategies.

// If throws AuthenticationTokenExpiredError, will be repeated after executing refreshAccessToken.

});If the call throws an exception not handled by the policy or fails to execute successfully within the specified parameters, the error gets rethrown.

- The app is a work in progress. There are still many essential things missing — input validation, tests, graceful error display, lots of UI elements, better caching — just to name a few.

- UI colors are supposed to change depending on which team community is selected. At the moment though all colors are simply hardcoded.

- The app hasn't been tested on IOS devices (even an emulator) as of yet, since I don't have a Mac, which is required to build an actual executable file. The app itself doesn't have any platform-specific code, though there are a couple of dependencies that do. I configured them according to the instructions, so the app should work fine on both Android and IOS.