| layout |

|---|

default |

{% include links %}

- TOC {:toc}

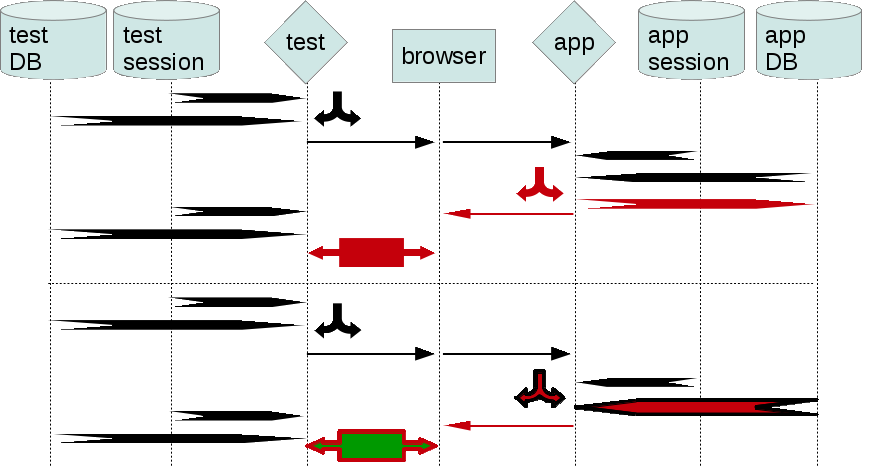

Time axis is vertical, from up downwards. Steps are grouped in runs, which are separated by a vertical dotted line.

A step is an operation, either

- data-based

- decision (can be random-based)

- GUI control-based (including generating contents, input values, page navigation)

- comparison (of the actual and expected contents)

The focus is on problems and complications in the testing process. Therefore diagrams omit any successful steps that are not relevant to demonstrating a problem.

Diagrams are as cut down as possible. There can be many variations of the same situation, all with the same idea. For example, there may be more/less buggy steps, but the overall pattern is the same. If a diagram doesn't indicate separate [script]/app sessions between runs, it's likely that a similar pattern applies, even if some of the runs happen to be in separate test/application sessions.

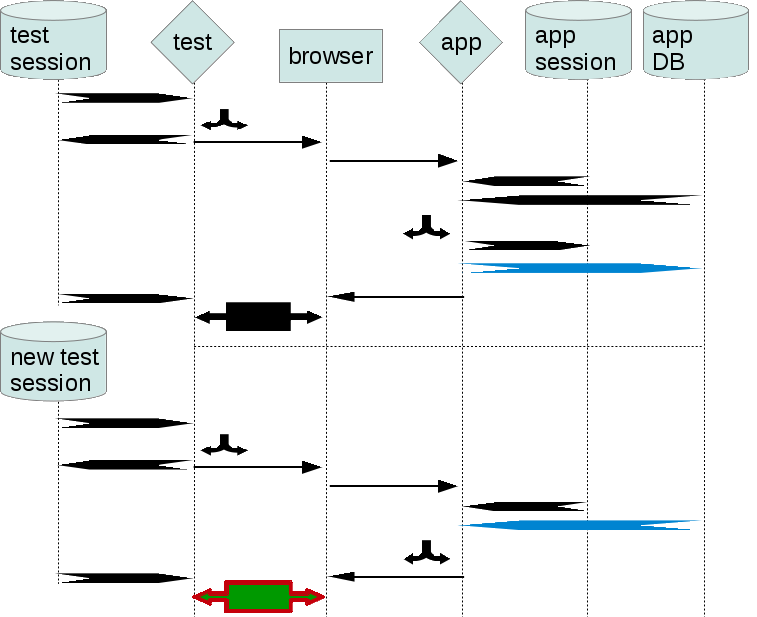

When demonstrating a feature/pattern of the QA process, it's often irrelevant whether a particular step is fully correct. So, if a step is 'correct enough' for the purpose of the example, it's drawn in black (or blue or yellow). Sometimes it's not obvious whether a step should be presented as correct. In such cases this documentation deems the correctness in the local context. An example is the first diagram with its second [script] run. Application data has been affected by the first script run and it is correct from the viewpoint of the app. The app data may seem to be incorrect for the script, but that's because the demonstrated framework is incapable of tracking app data (as opposed to SeLite). So we colour the app data as correct, and the script comparison as incorrect (false negative).

Referring to steps and their effects/side effects

- if effects of a step are important and are referred to later on, this colours the step in blue or yellow

- a correct step can have side effects/knock on effects that are not relevant to the feature/pattern in question

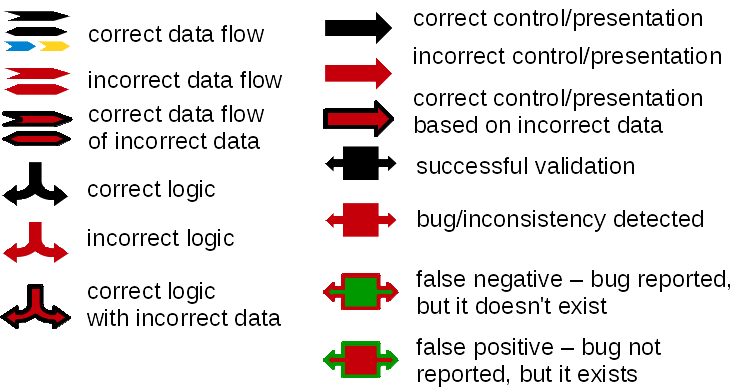

The following legend applies to all diagrams here.

Since the [script] has no DB, it 'loses the track' when its session ends. Successive separate script sessions will not know what will have been applied to [script DB] by earlier runs.

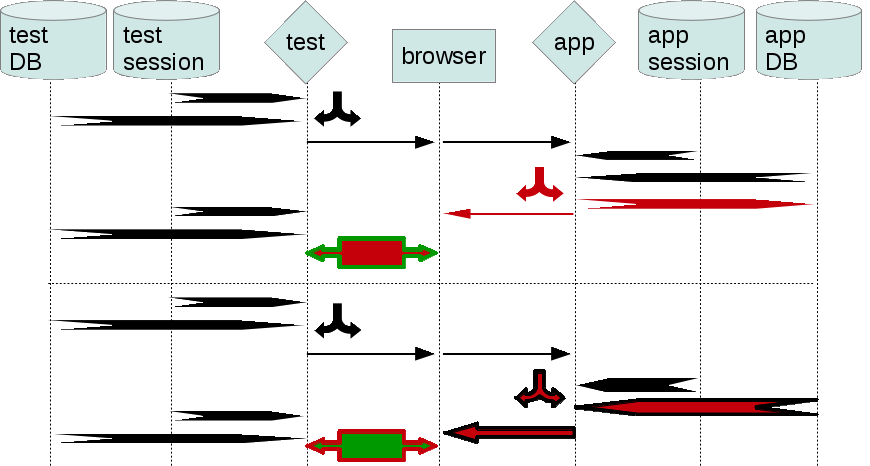

If a script run fails, it may confuse successive runs which would succeed otherwise (false negative).

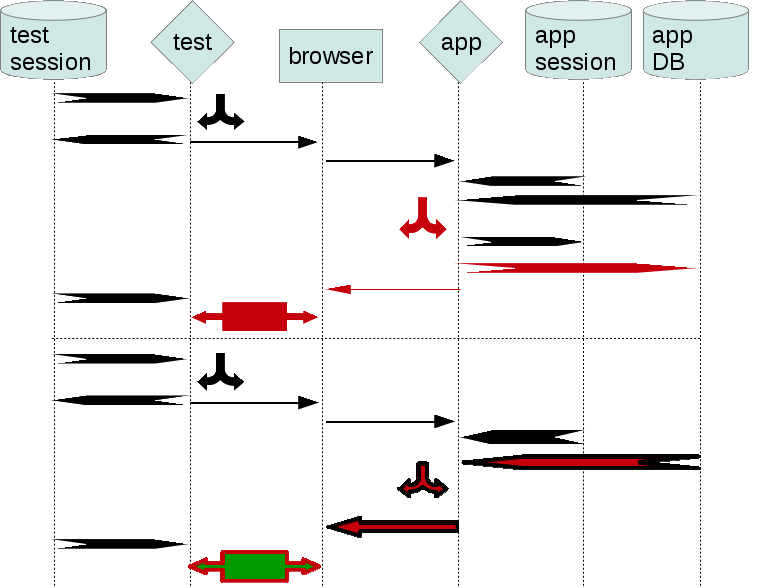

If [script] doesn't detect a bug straight away, it may not be discovered even though it made app data incorrect. The framework depends on the backdoor data from [app DB]. However, that shared data fools it. The script can't detect the incorrect data, because it has no other dataset to compare against. This is the main reason for SeLite.

Just as with other frameworks (listed here), if [script] fails, it may affect its further runs (which would succeed otherwise).

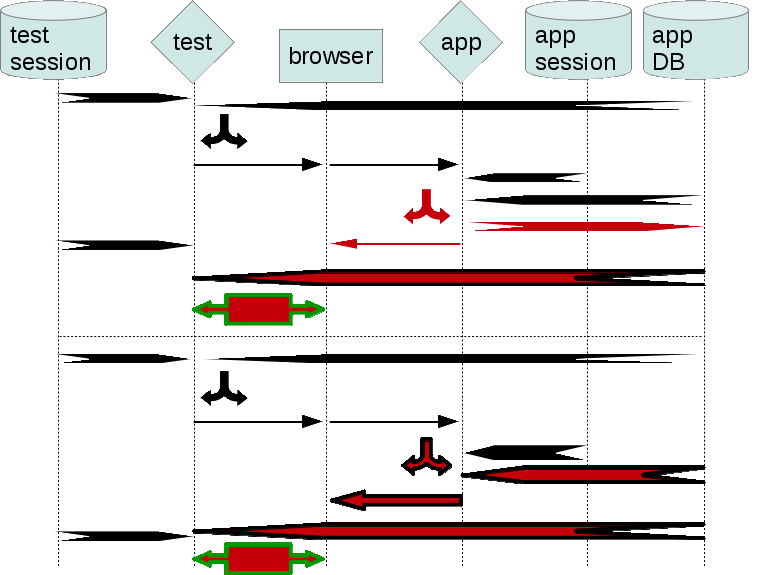

Knock-on effect of hidden errors

This is a type of bugs that can't be generally and easily detected without script having its own DB. SeLite is beneficial here.