Shiyu Mou

A class should have a primary responsibility and should not take up other responsibilities.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persistence_(computer_science)#cite_note-1

In computer science, persistence refers to the characteristic of state that outlives the process that created it. This is achieved in practice by storing the state as data in computer data storage. Programs have to transfer data to and from storage devices and have to provide mappings from the native programming-language data structures to the storage device data structures.

#include <iostream>

#include <fstream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <boost/lexical_cast.hpp>

using namespace std;

struct Journal

{

string title;

vector<string> entries;

explicit Journal(const string& title)

: title{title}

{

}

void add(const string& entry);

// persistence is a separate concern

void save(const string& filename);

};

void Journal::add(const string& entry)

{

static int count = 1;

entries.push_back(boost::lexical_cast<string>(count++)

+ ": " + entry);

}

void Journal::save(const string& filename)

{

ofstream ofs(filename);

for (auto& s : entries)

ofs << s << endl;

}

struct PersistenceManager

{

static void save(const Journal& j, const string& filename)

{

ofstream ofs(filename);

for (auto& s : j.entries)

ofs << s << endl;

}

};

void main()

{

Journal journal{"Dear Diary"};

journal.add("I ate a bug");

journal.add("I cried today");

//journal.save("diary.txt");

PersistenceManager pm;

pm.save(journal, "diary.txt");

}Here it's a bad idea to put persistence code in the class. Imagine you have hundreds of class and each of them has a persistence code. When your database changed, you have to go to all the hundreds class to modify them. It's a better diea to create another class for handling all the persistence code. This is called Separation of concerns.

class GfG

{

public:

GfG()

{cout << "Inside Constructor\n"; }

~GfG()

{cout << "Inside Destructor\n"; }

};

int main()

{

int x = 0;

if (x==0)

{

//case1: GfG obj;

//case2: static GfG obj;

}

cout << "End of main\n";

} Case1:

- Inside Constructor

- Inside Destructor

- End of main

Case2:

- Inside Constructor

- End of Main

- Inside Destructor

The object stays out of scope when declaring an object as static.

Just like the static data members or static variables inside the class, static member functions also does not depend on object of class. We are allowed to invoke a static member function using the object and the ‘.’ operator but it is recommended to invoke the static members using the class name and the scope resolution operator.

Static member functions are allowed to access only the static data members or other static member functions, they can not access the non-static data members or member functions of the class.

class GfG

{

public:

// static member function

static void printMsg()

{

cout<<"Welcome to GfG!";

}

};

// main function

int main()

{

// invoking a static member function

GfG::printMsg();

}Static member/member function in class can be called without creating an object.

But, static member is only declared in class, not defined, it has to be define outside using resolution scope. Check here for details: https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/static-data-members-c/ https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/cpp/cpp/static-members-cpp?view=vs-2019

When the constructor has one single argument, https://stackoverflow.com/questions/121162/what-does-the-explicit-keyword-mean

Class objects could also be initialized using assignment from a single value if they had a conversion constructor (prior to C++11, a constructor with a single parameter was called a conversion constructor):

```

class Foo

{

public:

// single parameter constructor, can be used as an implicit conversion

Foo (int foo) : m_foo (foo)

{

}

int GetFoo () { return m_foo; }

private:

int m_foo;

};

```

```

void DoBar (Foo foo)

{

int i = foo.GetFoo ();

}

```

```

int main ()

{

DoBar (42);

// expect type Foo, but now it still works! Because the

//constructor of foo takes int as a single argument.

}

```So the open closed principle basically states that your systems should be open to extensions so you should be able to extend systems by inheritance for example but closed for modification.

// open closed principle

// open for extension, closed for modification

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

enum class Color { red, green, blue };

enum class Size { small, medium, large };

struct Product

{

string name;

Color color;

Size size;

};

struct ProductFilter

{

typedef vector<Product*> Items;

Items by_color(Items items, const Color color)

{

Items result;

for (auto& i : items)

if (i->color == color)

result.push_back(i);

return result;

}

Items by_size(Items items, const Size size)

{

Items result;

for (auto& i : items)

if (i->size == size)

result.push_back(i);

return result;

}

Items by_size_and_color(Items items, const Size size, const Color color)

{

Items result;

for (auto& i : items)

if (i->size == size && i->color == color)

result.push_back(i);

return result;

}

};

template <typename T> struct AndSpecification;

template <typename T> struct Specification

{

virtual ~Specification() = default;

virtual bool is_satisfied(T* item) const = 0;

// new: breaks OCP if you add it post-hoc

/*AndSpecification<T> operator&&(Specification<T>&& other)

{

return AndSpecification<T>(*this, other);

}*/

};

// new:

template <typename T> AndSpecification<T> operator&&

(const Specification<T>& first, const Specification<T>& second)

{

return { first, second };

}

template <typename T> struct Filter

{

virtual vector<T*> filter(vector<T*> items,

Specification<T>& spec) = 0;

};

struct BetterFilter : Filter<Product>

{

vector<Product*> filter(vector<Product*> items,

Specification<Product> &spec) override

{

vector<Product*> result;

for (auto& p : items)

if (spec.is_satisfied(p))

result.push_back(p);

return result;

}

};

struct ColorSpecification : Specification<Product>

{

Color color;

ColorSpecification(Color color) : color(color) {}

bool is_satisfied(Product *item) const override {

return item->color == color;

}

};

struct SizeSpecification : Specification<Product>

{

Size size;

explicit SizeSpecification(const Size size)

: size{ size }

{

}

bool is_satisfied(Product* item) const override {

return item->size == size;

}

};

template <typename T> struct AndSpecification : Specification<T>

{

const Specification<T>& first;

const Specification<T>& second;

AndSpecification(const Specification<T>& first, const Specification<T>& second)

: first(first), second(second) {}

bool is_satisfied(T *item) const override {

return first.is_satisfied(item) && second.is_satisfied(item);

}

};

// new:

int main()

{

Product apple{"Apple", Color::green, Size::small};

Product tree{"Tree", Color::green, Size::large};

Product house{"House", Color::blue, Size::large};

const vector<Product*> all { &apple, &tree, &house };

BetterFilter bf;

ColorSpecification green(Color::green);

auto green_things = bf.filter(all, green);

for (auto& x : green_things)

cout << x->name << " is green\n";

SizeSpecification large(Size::large);

AndSpecification<Product> green_and_large(green, large);

//auto big_green_things = bf.filter(all, green_and_large);

// use the operator instead (same for || etc.)

auto spec = green && large;

for (auto& x : bf.filter(all, spec))

cout << x->name << " is green and large\n";

// warning: the following will compile but will NOT work

// auto spec2 = SizeSpecification{Size::large} &&

// ColorSpecification{Color::blue};

getchar();

return 0;

}https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/enum-classes-in-c-and-their-advantage-over-enum-datatype/

In practice, try to make as many functions const as possible. For example: getValue(), print(), etc... Const object can only call const functions. But const functions can be called by any object.

In C++, the only difference between struct and class is struct makes members public by default while class makes them private.

It depends. If you allocate them inside a function as local variables, for example

void somefunction(){ MyClass foo; …}they’ll be allocated on the stack. If you allocate them as global variables, such as

MyClass foo;void somefunction(){}they’ll be in the static area - neither the heap, nor the stack, but an area of fixed size allocated for this purpose when the program is loaded. If you allocate them inside a function using new, like this:

void somefunction(){ MyClass *foo = new MyClass(); … delete foo;}they’ll be on the heap.

The above policy applies to everything (int, string, etc) in C++.

Objects in a program should be replaceable with instances of their subtypes w/o altering the correctness of the program.

If a function takes a base class object as argument, then the function should also works with all the other subclass objects.

#include <iostream>

class Rectangle

{

protected:

int width, height;

public:

Rectangle(const int width, const int height)

: width{width}, height{height} { }

int get_width() const { return width; }

virtual void set_width(const int width) { this->width = width; }

int get_height() const { return height; }

virtual void set_height(const int height) { this->height = height; }

int area() const { return width * height; }

};

class Square : public Rectangle

{

public:

Square(int size): Rectangle(size,size) {}

void set_width(const int width) override {

this->width = height = width;

}

void set_height(const int height) override {

this->height = width = height;

}

};

struct RectangleFactory

{

static Rectangle create_rectangle(int w, int h);

static Rectangle create_square(int size);

};

void process(Rectangle& r)

{

int w = r.get_width();

r.set_height(10);

std::cout << "expected area = " << (w * 10)

<< ", got " << r.area() << std::endl;

}

int main()

{

Rectangle r{ 5,5 };

process(r);

Square s{ 5 };

process(s);

getchar();

return 0;

}- Expected 50, got 50

- Expected 50, got 100

Clients should not be forced to depend upon interfaces that they do not use. Avoid stuffing too much into a single interface.

#include <vector>

struct Document;

/*** bad interface, all subclass will has these 3 functions but usually only

one is needed. You have to leave the rest as empty or throw exceptions ***/

//struct IMachine

//{

// virtual void print(Document& doc) = 0;

// virtual void fax(Document& doc) = 0;

// virtual void scan(Document& doc) = 0;

//};

//

//struct MFP : IMachine

//{

// void print(Document& doc) override;

// void fax(Document& doc) override;

// void scan(Document& doc) override;

//};

// 1. Recompile

// 2. Client does not need this

// 3. Forcing implementors to implement too much

/*** better interface, seperate them ***/

struct IPrinter

{

virtual void print(Document& doc) = 0;

};

struct IScanner

{

virtual void scan(Document& doc) = 0;

};

struct Printer : IPrinter

{

void print(Document& doc) override;

};

struct Scanner : IScanner

{

void scan(Document& doc) override;

};

struct IMachine: IPrinter, IScanner

{

};

struct Machine : IMachine

{

IPrinter& printer;

IScanner& scanner;

Machine(IPrinter& printer, IScanner& scanner)

: printer{printer},

scanner{scanner}

{

}

void print(Document& doc) override {

printer.print(doc);

}

void scan(Document& doc) override;

};

// IPrinter --> Printer

// everything --> Machine- The high level modules should not depend on low level modules. Both should depend on abstractions

- Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.

The abstraction is also base class, interface. The idea is to make abstractions as generic as possible.

Low level structure: class that stores data, with some API functions for add data and get data.

High Level structure: perform some research on the data.

/***

Acknowledagement: This is a lecture note for course https://www.udemy.com/course/patterns-cplusplus/ by

@Dmitri Nesteruk

Title: Dependency Inversion Principle

// A. High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules.

// Both should depend on abstractions.

// B. Abstractions should not depend on details.

// Details should depend on abstractions.

Shiyu Mou

***/

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <tuple>

using namespace std;

enum class Relationship

{

parent,

child,

sibling

};

struct Person

{

string name;

};

/*** A bad idea that breaks dependency inversion principle***/

// low level module

struct Relationships // low level

{

vector<tuple<Person, Relationship, Person>> relations;

void add_parent_and_child(const Person& parent, const Person& child){

relations.push_back({parent, Relationship::parent, child});

realtions.push_back({child, Relationship::child, parent});

}

};

// high level research module

struct Research

{

Research(Relationships& relationships) // depend on low level

{

// depend on the low level details

// bad if the low level code decides to change

// the container of relations (map) or make it private

// then the high level code breaks

auto& relations = relationships.relations;

for (auto&& [first, rel, second] : relations)

{

if (first.name == "John" && rel == Relationship::parent)

{

cout << "John has a child called "<< second.name;

}

}

}

};

/*** A better idea that breaks dependency inversion principle***/

// now introduce an abstraction

struct RelationshipBrowser

{

virtual vector<Person> find_all_children_of(const string& name) = 0;

};

// low level

struct Relationships : RelationshipBrowser // low level

{

vector<tuple<Person, Relationship, Person>> relations;

void add_parent_and_child(const Person& parent, const Person& child){

relations.push_back({parent, Relationship::parent, child});

relations.push_back({child, Relationship::child, parent});

}

// move f

vector<Person> find_all_children_of(const string& name) override

{

vector<Person> result;

for (auto&& [first, rel, second]: relations)

{

if (first.name == name && rel == Relationships::parent)

{

result.push_back(second);

}

}

return result;

}

};

// high level

struct Research

{

// won't depend on details, now depends on abstraction, thanks to polymorphsim,

// you can pass subclass object here

Research(RelationshipBrowser& browser)

{

for (auto& child : browser.find_all_children_of("John"))

{

cout << "John has a child called " << child.name << endl;

}

}

};

int main(){

Person parent{"John"};

Person child1{"Chris"};

Person child2{"Matt"};

Relationships relationships;

relationships.add_parent_and_child(parent, child1);

relationships.add_parent_and_child(parent, child2);

Research _(relationships);

}- Deal with the creation (construction) of objects

- Explicit (constructor) vs implicit (DI, reflection, etc)

- Wholesale (single statement) vs piecewise (step-by-step)

- Concerned with the structure (e.g. class members).

- Many patterns are wrappers that mimic the underlying class' interface

- Stress the importance of good API design

They are all different, no central theme

-

Simple objects are simple and can be created in a single constructor call.

-

Other objects require a lot of ceremony to create

-

Having an object with 10 constructor arguments is not productive

-

Instead, opt for piecewise construction

-

Builder provides and API for constructing an object step-by-step

When piecewise object construction is complicated, provide an API for doing it succinctly .

Think the HtmlElement as a TreeNode, it has data and a vector of children. And let's say build a TreeNode is complicated. Instead of implementing add_child function inside TreeNode to fill all the children, we create a builder, keep a treeNode as a member, and provide API to such as add_child function there.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <sstream>

#include <memory>

using namespace std;

struct HtmlElement

{

string name;

string text;

vecotor<HtmlElement> elements;

HtmlElement() {}

HtmlElement(const string& name, const string& text): name(name), text(text){}

string str(int indent = 0) const

{

// some code

// in C++, str is usually for printing

}

};

struct HtmlBuilder

{

HtmlElement root;

HtmlBuilder(string rootname)

{

root.name = root_name;

}

void add_child(string child_name, string child_text)

{

HtmlElement e{child_name, child_text};

root.elements.emplace_back(e);

}

string str() {return root.str();}

};

int main()

{

// easier way

HtmlBuilder builder{ "ul" };

builder.add_child("li", "hello");

builder.add_child("li", "world");

cout << builder.str() << endl;

return 0;

}Fluent interface is something like object.add().add() so you don't need to do object.add(); object.add();This is achieved by returning either a reference or a pointer.

The static member in HtmlElement gives users a hint to use the builder to build object.

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <sstream>

#include <memory>

using namespace std;

// the struct here is just used for modeling this data.

struct HtmlElement

{

string name;

string text;

vecotor<HtmlElement> elements;

HtmlElement() {}

HtmlElement(const string& name, const string& text): name(name), text(text){}

string str(int indent = 0) const

{

// some code

}

// give costumer a hint to use the builder

static HtmlBuilder build(string root_name)

{

return {root_name}; // here would be an implicit conversion for HtmlBuilder

}

};

// use a builder to actually build it

struct HtmlBuilder

{

HtmlElement root;

HtmlBuilder(string rootname)

{

root.name = root_name;

}

// fluent builder #1

// reference

HtmlBuilder& add_child(string child_name, string child_text)

{

HtmlElement e{child_name, child_text};

root.elements.emplace_back(e);

return *this;

}

string str() {return root.str();}

// the operator here convert builder to element.

operator HtmlElement() const {return root;}

};

int main()

{

// this way you get a builder

auto builder = HtmlElement::build('ul').add.child("", "").add.child("", "");

// if you want to get a HtmlElement, add an operator

HtmlElement elem = HtmlElement::build('ul').add.child("", "").add.child("", "");

return 0;

}Now use pointer

#include <iostream>

#include <string>

#include <vector>

#include <sstream>

#include <memory>

using namespace std;

struct HtmlElement

{

string name;

string text;

vecotor<HtmlElement> elements;

HtmlElement() {}

HtmlElement(const string& name, const string& text): name(name), text(text){}

string str(int indent = 0) const

{

// some code

}

// give costumer a hint to use the builder

static unique_ptr<HtmlElement> build(string root_name)

{

return make_unique<HtmlElement>(root_name);

}

};

struct HtmlBuilder

{

HtmlElement root;

HtmlBuilder(string rootname)

{

root.name = root_name;

}

// fluent builder #2

// pointer

HtmlBuilder* add_child_2(string child_name, string child_text)

{

HtmlElement e{ child_name, child_text };

root.elements.emplace_back(e);

return this;

}

string str() {return root.str();}

operator HtmlElement() const {return root;}

};

int main()

{

// fluent builder #2

auto builder2 = HtmlElement::build("ul")

->add_child_2("li", "hello")->add_child_2("li", "world");

cout << builder2 << endl;

return 0;

}To force users to use our builder API by HtmlBuilder::build(), make sure they can only construct the HtmlElement through builder.

Hide the constructor of HtmlElement. So the user cannot build HtmlElement directly. To make builder work, we need to make builder a friend of HtmlElement.

class HtmlElement

{

friend class HtmlBuilder;

string name;

string text;

vecotor<HtmlElement> elements;

HtmlElement() {}

HtmlElement(const string& name, const string& text): name(name), text(text){}

public:

string str(int indent = 0) const

{

// some code

}

// give costumer a hint to use the builder

static HtmlBuilder create(string root_name)

{

return {root_name}; // here would be an implicit conversion for HtmlBuilder

}

};

class HtmlBuilder

{

HtmlElement root;

public:

HtmlBuilder(string rootname)

{

root.name = root_name;

}

HtmlBuilder& add_child(string child_name, string child_text)

{

HtmlElement e{child_name, child_text};

root.elements.emplace_back(e);

return *this;

}

HtmlElement build() {return root;}

string str() {return root.str();}

operator HtmlElement() const {return root;}

};

int main()

{

// if you want to get a HtmlElement, add an operator

HtmlElement elem = HtmlElement::build('ul').add.child("", "").add.child("", "").build();

}In C++ STL, there is priority_queue that can directly be used to implement Max Heap.

// C++ program to show that priority_queue is by

// default a Max Heap

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

// Driver code

int main ()

{

// Creates a max heap

priority_queue <int> pq;

pq.push(5);

pq.push(1);

pq.push(10);

pq.push(30);

pq.push(20);

// One by one extract items from max heap

while (pq.empty() == false)

{

cout << pq.top() << " ";

pq.pop();

}

return 0;

}

// Output: 30 20 10 5 1How to implement Min Heap? priority_queue supports a constructor that requires two extra arguments to make it min heap.

// priority_queue <Type, vector<Type>, ComparisonType > min_heap;

priority_queue <int, vector<int>, greater<int> > pq; How to make a min heap of user defined class? Let us consider below example where we build a min heap of 2 D points ordered by X axis.

// C++ program to use priority_queue to implement Min Heap

// for user defined class

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

// User defined class, Point

class Point

{

int x;

int y;

public:

Point(int _x, int _y)

{

x = _x;

y = _y;

}

int getX() const { return x; }

int getY() const { return y; }

};

// To compare two points

class myComparator

{

public:

int operator() (const Point& p1, const Point& p2)

{

return p1.getX() > p2.getX();

}

};

// Driver code

int main ()

{

// Creates a Min heap of points (order by x coordinate)

priority_queue <Point, vector<Point>, myComparator > pq;

// Insert points into the min heap

pq.push(Point(10, 2));

pq.push(Point(2, 1));

pq.push(Point(1, 5));

// One by one extract items from min heap

while (pq.empty() == false)

{

Point p = pq.top();

cout << "(" << p.getX() << ", " << p.getY() << ")";

cout << endl;

pq.pop();

}

return 0;

} If defined inside class, the functions are automatically inline (unless complicated).

Function definition is better outside the class. That way your code can remain safe if required. The header file should just give declarations.

Suppose someone wants to use your code, you can just give him the .h file and the .obj file (obtained after compilation) of your class. He does not need the .cpp file to use your code.

That way your implementation is not visible to anyone else.

https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/structured-binding-c/

It doesn't work for vector. Because this only works for structures that are known at compile time. In compile time, the size of vector is unknown.

&& is a new reference operator defined in the C++11 standard. int&& a means "a" is an r-value reference. && is normally only used to declare a parameter of a function. And it only takes an r-value expression.

Simply put, an r-value is a value that doesn't have a memory address. E.g. the number 6, and character 'v' are both r-values. int a, a is an l-value, however (a+2) is an r-value. For example:

void foo(int&& a)

{

//Some magical code...

}

int main()

{

int b;

foo(b); //Error. An rValue reference cannot be pointed to a lValue.

foo(5); //Compiles with no error.

foo(b+3); //Compiles with no error.

int&& c = b; //Error. An rValue reference cannot be pointed to a lValue.

int&& d = 5; //Compiles with no error.

}A Plain Old Data Structure in C++ is an aggregate class that contains only PODS as members, has no user-defined destructor, no user-defined copy assignment operator, and no non static members of pointer-to-member type.

struct bar { int a_; double b_;};

bar b{ 42, 1.2 };In C++03, initialization of variables has been different for different kinds of variables, and sometimes it was not even possible. With C++11 we got so-called uniform initialization, which attempts to make the whole topic a bit easier for developers.

Uniform initialization is pretty simple: you can initialize practically everything with arguments in curly braces. The compiler then will do just the right thing.

# in the past

std::string s1("test"); // direct initialization

std::string s2 = "test"; // copy initializationTo uniformly initialize objects regardless of their type, use the brace-initialization form {} that can be used for both direct initialization and copy initialization. When used with brace initialization, these are called direct list and copy list initialization.

They are equal in the sense that they do mostly the same thing. But they're not technically equal; copy-list-initialization cannot call explicit constructors. So if the selected constructor were explicit, the code would fail to compile in the copy-list-initialization cases.

T object {other}; // direct list initialization

T object = {other}; // copy list initializationclass foo

{

int a_;

double b_;

public:

foo():a_(0), b_(0) {}

foo(int a, double b = 0.0):a_(a), b_(b) {}

};

foo f1{};

foo f2{ 42, 1.2 };

foo f3{ 42 };

struct bar

{

int a_;

double b_;

};

bar b{ 42, 1.2 };Initialization of standard containers, such as the vector and the map also shown above, is possible because all standard containers have an additional constructor in C++11 that takes an argument of type std::initializer_list. This is basically a lightweight proxy over an array of elements of type T const. These constructors then initialize the internal data from the values in the initializer list.

// so you can do

vector<int> a{1, 2, 3, 4};

map<int, int> b{{1, 2}, {2, 4}};In C++11

The following sample shows several examples of direct-list-initialization and copy-list-initialization. In C++11, the deduced type of all these expressions is std::initializer_list.

auto a = {42}; // std::initializer_list<int>

auto b {42}; // std::initializer_list<int>

auto c = {4, 2}; // std::initializer_list<int>

auto d {4, 2}; // std::initializer_list<int>C++17 has changed the rules for list initialization, differentiating between the direct- and copy-list-initialization. The new rules for type deduction are as follows:

- for copy list initialization auto deduction will deduce a

std::initializer_listif all elements in the list have the same type, or be ill-formed. - for direct list initialization auto deduction will deduce a

Tif the list has a single element, or be ill-formed if there is more than one element.

Base on the new rules, the previous examples would change as follows: a and c are deduced as std::initializer_list; b is deduced as an int; d, which uses direct initialization and has more than one value in the brace-init-list, triggers a compiler error.

auto a = {42}; // std::initializer_list<int>

auto b {42}; // int

auto c = {4, 2}; // std::initializer_list<int>

auto d {4, 2}; // error, too manyHere’s what actually happens when base is instantiated:

- Memory for base is set aside

- The appropriate Base constructor is called

- The initialization list initializes variables

- The body of the constructor executes

- Control is returned to the caller

Here’s what actually happens when derived is instantiated:

- Memory for derived is set aside (enough for both the Base and Derived portions)

- The appropriate Derived constructor is called

- The Base object is constructed first using the appropriate Base constructor. If no base constructor is specified, the default constructor will be used.

- The initialization list initializes variables

- The body of the constructor executes

- Control is returned to the caller

class Base

{

public:

int m_id;

Base(int id=0)

: m_id{ id }

{

}

int getId() const { return m_id; }

};class Derived: public Base

{

public:

double m_cost;

Derived(double cost=0.0, int id=0)

// does not work

: m_cost{ cost }, m_id{ id }

{

}

double getCost() const { return m_cost; }

};

class Derived: public Base

{

public:

double m_cost;

Derived(double cost=0.0, int id=0)

: m_cost{ cost }

{

// work but bad, what is m_id is const or reference?

m_id = id;

}

double getCost() const { return m_cost; }

};When derived class is initiated, first the derived class constructor is called, but not initialized, then base class constructor is called, and finish the initialization, then derived constructor finish the initialization. If not specific, the default constructor of derived class will be called/

Fortunately, C++ gives us the ability to explicitly choose which Base class constructor will be called! To do this, simply add a call to the base class Constructor in the initialization list of the derived class:

class Derived: public Base

{

public:

double m_cost;

// we can even make m_id private in base class

Derived(double cost=0.0, int id=0)

: Base{ id }, // Call Base(int) constructor with value id!

m_cost{ cost }

{

}

double getCost() const { return m_cost; }

};The base class constructor Base(int) will be used to initialize m_id to 5, and the derived class constructor will be used to initialize m_cost to 1.3!

- Memory for derived is allocated.

- The Derived(double, int) constructor is called, where cost = 1.3, and id = 5

- The compiler looks to see if we’ve asked for a particular Base class constructor. We have! So it calls Base(int) with id = 5.

- The base class constructor initialization list sets m_id to 5

- The base class constructor body executes, which does nothing

- The base class constructor returns

- The derived class constructor initialization list sets m_cost to 1.3

- The derived class constructor body executes, which does nothing

- The derived class constructor returns

Builder with multiple concrete builder classes inheriting from Builder. These classes contain the functionality to create a particular complex product.

- Product – The product class defines the type of the complex object that is to be generated by the builder pattern.

- Builder – This abstract base class defines all of the steps that must be taken in order to correctly create a product. Each step is generally abstract as the actual functionality of the builder is carried out in the concrete subclasses. The GetProduct method is used to return the final product. The builder class is often replaced with a simple interface.

- ConcreteBuilder – There may be any number of concrete builder classes inheriting from Builder. These classes contain the functionality to create a particular complex product.

- Director – The director class controls the algorithm that generates the final product object. A director object is instantiated and its Construct method is called. The method includes a parameter to capture the specific concrete builder object that is to be used to generate the product. The director then calls methods of the concrete builder in the correct order to generate the product object. On completion of the process, the GetProduct method of the builder object can be used to return the product.

http://fusharblog.com/3-ways-to-define-comparison-functions-in-cpp/

When std::vector’s internal memory completely finishes then it increases the size of its memory. To do that it performs following steps,

1.) It will allocate a bigger chunk of memory on heap i.e. almost double the size of previously allocated. 2.) Then it copies all the elements from old memory location to new one. Yes it copies them, so in case our elements are user defined objects then their copy constructor will be called. Which makes this step quite heavy in terms of speed. 3.) Then after successful copying it deletes the old memory.

// Initialize a vector with 10 ints of value 0

std::vector<int> vecOfRandomNums(10);

std::generate(vecOfRandomNums.begin(), vecOfRandomNums.end(), []() {

return rand() % 100;

});struct RandomGenerator {

int maxValue;

RandomGenerator(int max) :

maxValue(max) {}

int operator()() const {

return rand() % maxValue;

}

};

// Generate 10 random numbers by a Functor and fill it in vector

std::generate(vecOfRandomNums.begin(), vecOfRandomNums.end(), RandomGenerator(500));A functor (or function object) is a C++ class that acts like a function. Functors are called using the same old function call syntax. To create a functor, we create an object that overloads the operator().

#include <iostream>

class myFunctorClass

{

int _x;

public:

myFunctorClass (int x) : _x( x ) {}

int operator() (int y) { return _x + y; }

// I'm overloading this operator "()", and (int y) is arugment

};

int main()

{

// myFunctorClass addFive( 5 );

std::cout << myFunctorClass(5)(6);

return 0;

}

// same as

int main()

{

myFunctorClass object( 5 );

std::cout << object(6);

return 0;

}#include<iostream>

#include<stdio.h>

using namespace std;

class Test

{

public:

Test() {}

Test(const Test &t)

{

cout<<"Copy constructor called "<<endl;

}

Test& operator = (const Test &t)

{

cout<<"Assignment operator called "<<endl;

return *this;

}

};

// Driver code

int main()

{

Test t1, t2;

t2 = t1; // assignment

Test t3 = t1; // copy

getchar();

return 0;

} Assignment operator called Copy constructor called

Assign happens when an object already has content. When assign, inside the program creates a clone of t1, then destructs the resources holds by t2 originally, then attach the clone to t1.

They all have a default one by compiler.

- All STL contains always stores the copy of inserted objects not the actual one. So, whenever we insert any element or object in container then its copy constructor is called to create a copy and then this copy is inserted in the container.

- While insertion in std::vector it might be possible that storage relocation takes place internally due to insufficient space. In such cases assignment operator will be called on objects inside the container to copy them from one location to another.

When is copy constructor called? In C++, a Copy Constructor may be called in following cases: \1. When an object of the class is returned by value. \2. When an object of the class is passed (to a function) by value as an argument. \3. When an object is constructed based on another object of the same class. \4. When the compiler generates a temporary object.

When is user-defined copy constructor needed? If we don’t define our own copy constructor, the C++ compiler creates a default copy constructor for each class which does a member-wise copy between objects. The compiler created copy constructor works fine in general. We need to define our own copy constructor only if an object has pointers or any runtime allocation of the resource like file handle, a network connection, etc. Deep copy.

Suppose X is a class that holds a pointer or handle to some resource, say, m_pResource. By a resource, I mean anything that takes considerable effort to construct, clone, or destruct. A good example is std::vector, which holds a collection of objects that live in an array of allocated memory. Then, logically, the copy assignment operator for X looks like this:

X& X::operator=(X const & rhs)

{

// [...]

// Make a clone of what rhs.m_pResource refers to.

// Destruct the resource that m_pResource refers to.

// Attach the clone to m_pResource.

// [...]

}Similar reasoning applies to the copy constructor. Now suppose X is used as follows:

X foo();

X x;

// perhaps use x in various ways

x = foo();The last line above

- clones the resource from the temporary returned by

foo, - destructs the resource held by

xand replaces it with the clone, - destructs the temporary and thereby releases its resource.

Rather obviously, it would be ok, and much more efficient, to swap resource pointers (handles) between x and the temporary, and then let the temporary's destructor destruct x's original resource. In other words, in the special case where the right hand side of the assignment is an rvalue, we want the copy assignment operator to act like this:

// [...]

// swap m_pResource and rhs.m_pResource

// [...] This is called move semantics. With C++11, this conditional behavior can be achieved via an overload:

RHS here is called a r_value reference

X& X::operator=(X && rhs)

{

// [...]

// swap this->m_pResource and rhs.m_pResource

// [...]

}The content is actually swapped rather than copied. Thus faster.

- Constructor

- Destructor

- Copy constructor

- Assign Operator

- Move constructor

- Move assignment

The c++ complier has Return Value Optimization (RVO) which will automatically avoid copy by make the return value a r_value. Check c++ copy elision

In case class T has move constructor not deleted, and notice t is a local variable that return t is eligible for copy elision, it move constructs the returned object just like return std::move(t); does. However return t; is still eligible to copy/move elision, so the construction may be omitted, while return std::move(t) always constructs the return value using move constructor.

In case move constructor in class T is deleted but copy constructor available, return std::move(t); will not compile, while return t; still compiles using copy constructor.

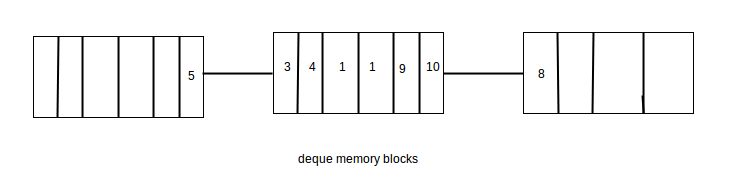

How std::deque works internally

Now a question rises how high deque is able to give good performance for insertion and deletion at both ends? To know the answer we need to know little internal implementation of dequeue.

A deque is generally implemented as a collection of memory blocks. These memory blocks contains the elements at contiguous locations.

When we create a deque object it internally allocates a memory block to store the elements at contigious location.

- When we insert an element in end it stores that in allocated memory block untill it gets filled and when this memory block gets filled with elements then it allocates a new memory block and links it with the end of previous memory block. Now further inserted elements in the back are stored in this new memory block.

- When we insert an element in front it allocates a new memory block and links it with the front of previous memory block. Now further inserted elements in the front are stored in this new memory block unless it gets filled.

- Consider deque as a linked list of vectors i.e. each node of this linked list is a memory block that store elements at contiguous memory location and each of the memory block node is linked with its previous and next memory block node.

Therefore, insertion at front is fast as compared to vector because it doesn’t need the elements to shift by 1 in current memory block to make space at front. It just checks if any space is left at left of first element in current memory block, if not then allocates a new memory block.

#include <memory>

struct Task

{

int mId;

Task(int id ) :mId(id)

{std::cout<<"Task::Constructor"<<std::endl;}

~Task()

{std::cout<<"Task::Destructor"<<std::endl;}

};

int main()

{

// Create a unique_ptr object through raw pointer

std::unique_ptr<Task> taskPtr(new Task(23));

//Access the element through unique_ptr

int id = taskPtr->mId;

// move ownership

std::unique_ptr<Task> taskPtr4 = std::move(taskPtr);

// Reseting the unique_ptr will delete the associated

// raw pointer and make unique_ptr object empty

taskPtr.reset();

// Release the ownership of object from raw pointer

// it will return a raw pointer

Task * ptr = taskPtr5.release();

delete ptr;

return 0;

}Shared Pointer

// create shared pointer

shared_ptr<int> ptr1(new int(1));

// count # of owners

ptr1.use_count();

shared_ptr<int> ptr2 = make_shared<int> (2);

// reset will decrease the count by 1

ptr2.reset();In the following method, we have to write a separate function to do this

#include <iostream>

#include "vector"

using namespace std;

void display(int a)

{

cout<<a<<" ";

}

using namespace std;

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

vector<int> vect{1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

for_each(vect.begin(), vect.end(), &display);

// or for_each(vect.begin(), vect.end(), display);

}

output: 1 2 3 4 5;Instead, we can use lambda function to embedded the function directly.

[](int x) {

std::cout<<x<<" ";

}- [] is used to pass the outer scope elements

- (int x) shows argument x is passed

#include <iostream>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

vector<int> vect{1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

for_each(vect.begin(), vect.end(), [](int x){x++; cout<<x<<" ";});

}[=](int &x) {

// All outer scope elements has been passed by value

}[&](int &x) {

// All outer scope elements has been passed by reference

}#include <iostream>

int main() {

int arr[] = { 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 };

int mul = 5;

std::for_each(arr, arr + sizeof(arr) / sizeof(int), [&](int x) {

std::cout<<x<<" ";

// Can modify the mul inside this lambda function because

// all outer scope elements has write access here.

mul = 3;

});

std::cout << std::endl;

std::for_each(arr, arr + sizeof(arr) / sizeof(int), [=](int &x) {

x= x*mul;

// Can not modify the mul inside this lambda function because

// all outer scope elements has read only access here

});

std::cout << std::endl;

std::for_each(arr, arr + sizeof(arr) / sizeof(int), [](int x) {

// No access to mul inside this lambda function because

// all outer scope elements are not visible here.

//std::cout<<mul<<" ";

});

std::cout << std::endl;

}- Create thread

void thread_function()

{

for (int i=0; i<10; i++) cout<<i<<" ";

cout<<"t1: "<<this_thread::get_id()<<endl;

}

class functor

{

public:

void operator() ()

{

for (int i=10; i<20; i++) cout<<i<<" ";

cout<<endl;

}

};

int main()

{

// function pointer

thread t1{&thread_function};

t1.join();

// functor

thread t2{functor()};

cout<<"t2: "<<t2.get_id()<<endl;

t2.join();

// lambda function

thread t3{[](){

for (int i=100; i<110; i++) cout<<i<<" ";

cout<<endl;

}};

cout<<"t3: "<<t3.get_id()<<endl;

t3.join();

return 0;

}Use join in most cases.

detach() is mainly useful when you have a task that has to be done in background, but you don't care about its execution. This is usually a case for some libraries. They may silently create a background worker thread and detach it so you won't even notice it.

You cannot join or detach a thread that is already joined or detached. It will cause the program to terminate. So check if it's joinable first.

std::thread threadObj( (WorkerThread()) );

if(threadObj.joinable())

{

std::cout<<"Detaching Thread "<<std::endl;

threadObj.detach();

}

if(threadObj.joinable())

{

std::cout<<"Detaching Thread "<<std::endl;

threadObj.detach();

}

std::thread threadObj2( (WorkerThread()) );

if(threadObj2.joinable())

{

std::cout<<"Joining Thread "<<std::endl;

threadObj2.join();

}

if(threadObj2.joinable())

{

std::cout<<"Joining Thread "<<std::endl;

threadObj2.join();

}The argument is passed by value by default.

void threadCallback(int x, std::string str)

{

std::cout<<"Passed Number = "<<x<<std::endl;

std::cout<<"Passed String = "<<str<<std::endl;

}

int main()

{

int x = 10;

std::string str = "Sample String";

std::thread threadObj(threadCallback, x, str);

threadObj.join();

return 0;

}void thread_function(int x)

{cout<<x<<endl;}

class functor

{

public:

void operator() (int x)

{cout<<x<<endl;}

};

int main()

{

// function pointer

thread t1{&thread_function, 1};

t1.join();

// functor

thread t2{functor(), 10};

t2.join();

// lambda function

thread t3([](int y) {cout<<y<<endl;},

20);

t3.join();

return 0;

}To pass by reference:

void threadCallback(int const & x)

{

int & y = const_cast<int &>(x);

y++;

std::cout<<"Inside Thread x = "<<x<<std::endl;

}

int main()

{

int x = 9;

std::thread t1(threadCallback, std::ref(x));

t1.join();

return 0;

}Don’t pass addresses of variables from local stack to thread’s callback function. Because it might be possible that local variable in Thread 1 goes out of scope but Thread 2 is still trying to access it through it’s address.

void newThreadCallback(int * p)

{

std::cout<<"Inside Thread : "" : p = "<<p<<std::endl;

std::chrono::milliseconds dura( 1000 );

std::this_thread::sleep_for( dura );

*p = 19;

}

void startNewThread()

{

int i = 10;

std::cout<<"Inside Main Thread : "" : i = "<<i<<std::endl;

std::thread t(newThreadCallback,&i);

t.join();

// or t.detach();

std::cout<<"Inside Main Thread : "" : i = "<<i<<std::endl;

}

int main()

{

startNewThread();

std::chrono::milliseconds dura( 2000 );

std::this_thread::sleep_for( dura );

return 0;

}

// output

// if join()

Inside Main Thread : : i = 10

Inside Thread : : p = 0x7ffee71267bc

Inside Main Thread : : i = 19

// if detach

Inside Main Thread : : i = 10

Inside Main Thread : : i = 10

Inside Thread : : p = 0x7ffee75627bc

Pass the pointer to member function as callback function and pass pointer to Object as second argument.

class foo {

public:

foo(){}

foo(const foo& obj){}

void thread_fun(int x) {}

}

int main(){

foo obj;

std::thread t1{&foo::thread_fun, &obj, 10};

t1.join();

return 0;

}class wallet

{

int money;

mutex m;

wallet() : money(0){}

void addMoney(int x){

m.lock();

money++;

m.unlock();

}

// or use lock_guard

void addMoney2(int x){

// automatically locked in the constructor

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> guard(m);

money++;

// goes out of scope, destuctor automatically unlock

}Suppose we are building a network based application. This application does following tasks

- Perform some handshaking with server

- Load data from XML files

- Do processing on the data loaded from XML

Task 1 and task 2 -> parallel.

Task 3 depends on task 2.

Thread 1:

- Handshake

- Wait for thread 2 to finish

- Do some work on data

Thread 2:

- Load data from XML

- Notify thread 1.

Option1: global variable with mutex

Cons: cost a lot CPU resources for the while loop (lock and unlock)

class App

{

std::mutex m;

bool done;

public:

App(): done(false){}

void loadData(){

// function for thread 2

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(1000));

std::cout<<" loading xml"<<std::endl;

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> guard(m);

done = true;

}

void mainTask(){

std::cout<<" handshaking "<<std::endl;

std::cout<<" handshaking finished "<<std::endl;

m.lock();

while (!done) {

m.unlock();

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(1000));

m.lock();

}

m.unlock();

std::cout<<" data loaded, start processing"<<std::endl;

}

};

int main(){

App app;

std::thread t1{&App::mainTask, &app};

std::thread t2{&App::loadData, &app};

t2.join();

t1.join();

return 0;

}

/***

handshaking

handshaking finished

loading xml

data loaded, start processing

/lock_guard and unique_lock are pretty much the same thing; lock_guardis a restricted version with a limited interface.

A lock_guard always holds a lock from its construction to its destruction. A unique_lock can be created without immediately locking, can unlock at any point in its existence, and can transfer ownership of the lock from one instance to another.

So you always use lock_guard, unless you need the capabilities of unique_lock. A condition_variable needs a unique_lock because it needs to lock and unlock it while wait.

#include "condition_variable"

class App

{

std::mutex m;

std::condition_variable cv;

bool done;

public:

App(): done(false){}

void loadData(){

// function for thread 2

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(1000));

std::cout<<" start loading xml"<<std::endl;

std::lock_guard<std::mutex> guard(m);

// or

// std::unique_lock<std::mutex> guard(m);

// here doesn't matter

done = true;

cv.notify_all();

// cv.notify_one();

}

void mainTask(){

std::cout<<" handshaking "<<std::endl;

std::cout<<" handshaking finished "<<std::endl;

std::unique_lock<std::mutex> u_lock(m);

// condition variable requires unique_lock

// option 1: cv.wait(u_lock, std::bind(&App::isDone, this));

// option 2:

while (!done) cv.wait(u_lock);

std::cout<<" data loaded, start processing"<<std::endl;

}

// bool isDone() {return done;}

};

int main(){

App app;

std::thread t1{&App::mainTask, &app};

std::thread t2{&App::loadData, &app};

t2.join();

t1.join();

return 0;

}Can we do this even more easier?

#include "future"

class App

{

std::promise<void> p1;

public:

void loadData(){

// function for thread 2

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(1000));

std::cout<<" start loading xml"<<std::endl;

p1.set_value();

}

void mainTask(){

std::cout<<" handshaking "<<std::endl;

std::cout<<" handshaking finished "<<std::endl;

p1.get_future().wait();

std::cout<<" data loaded, start processing"<<std::endl;

}

};

int main(){

App app;

std::thread t1{&App::mainTask, &app};

std::thread t2{&App::loadData, &app};

t2.join();

t1.join();

return 0;

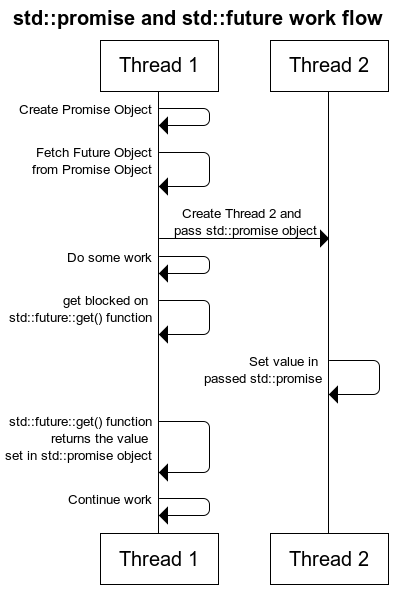

}Many times we encounter a situation where we want a thread to return a result.

1.) Old Way : Share data among threads using pointer

Pass a pointer to the new thread and this thread will set the data in it. Till then in main thread keep on waiting using a condition variable. When new thread sets the data and signals the condition variable, then main thread will wake up and fetch the data from that pointer.

To do a simple thing we used a condition variable, a mutex and a pointer i.e. 3 items to catch a returned value. Now suppose we want this thread to return 3 different values at different point of time then problem will become more complex. Could there be a simple solution for returning the value from threads.

2.) C++11 Way : Using std::future and std::promise

Actually a std::future object internally stores a value that will be assigned in future and it also provides a mechanism to access that value i.e. using get() member function. But if somebody tries to access this associated value of future through get() function before it is available, then get() function will block until it's available.

A std::promise object shares data with its associated std::future object.

As of now this promise object doesn’t have any associated value. But it gives a promise that somebody will surely set the value in it and once its set then you can get that value through associated std::future object.

class App

{

std::promise<int> p1;

public:

void loadData(){

// function for thread 2

std::this_thread::sleep_for(std::chrono::milliseconds(1000));

std::cout<<"start loading xml"<<std::endl;

p1.set_value(35);

}

void mainTask(){

std::cout<<"handshaking "<<std::endl;

std::cout<<"handshaking finished "<<std::endl;

std::future<int> ftr = p1.get_future();

// get() is the command that will block the thread until value is set

std::cout<<ftr.get()<<std::endl;

std::cout<<"data loaded, start processing"<<std::endl;

}

};

int main(){

App app;

std::thread t1{&App::mainTask, &app};

std::thread t2{&App::loadData, &app};

t2.join();

t1.join();

return 0;

}

/***

handshaking

handshaking finished

start loading xml

35

data loaded, start processing

/If it's not a class, pass the promise as a pointer of reference

void foo(std::promise<int>& p){

std::cout<<"inside thread"<<std::endl;

p.set_value(35);

}

int main(){

std::cout<<"main thread"<<std::endl;

std::promise<int> p;

std::future<int> ftr = p.get_future();

std::thread t1{foo, std::ref(p)};

int res = ftr.get();

std::cout<<"the result from thread is "<<res<<std::endl;

t1.join();

return 0;

}void initiazer(std::promise<int> * promObj)

{

std::cout<<"Inside Thread"<<std::endl; promObj->set_value(35);

}

int main()

{

std::promise<int> promiseObj;

std::future<int> futureObj = promiseObj.get_future();

std::thread th(initiazer, &promiseObj);

std::cout<<futureObj.get()<<std::endl;

th.join();

return 0;

}Need of std::async()

Suppose we have to fetch some data (string) from DB and some from files in file-system. Then I need to merge both the strings and print.

In a single thread we will do like this,

#include <chrono>

#include <thread>

using namespace std::chrono;

std::string fetchDataFromDB(std::string recvdData)

{

// Make sure that function takes 5 seconds to complete

std::this_thread::sleep_for(seconds(5));

//Do stuff like creating DB Connection and fetching Data

return "DB_" + recvdData;

}

std::string fetchDataFromFile(std::string recvdData)

{

// Make sure that function takes 5 seconds to complete

std::this_thread::sleep_for(seconds(5));

//Do stuff like fetching Data File

return "File_" + recvdData;

}

int main()

{

//Fetch Data from DB

std::string dbData = fetchDataFromDB("Data");

//Fetch Data from File

std::string fileData = fetchDataFromFile("Data");

return 0;

}

/***

Takes 10 seconds to do both

/std::async() does following things,

- It automatically creates a thread (Or picks from internal thread pool) and a promise object for us.

- Then passes the std::promise object to thread function and returns the associated std::future object.

- When our passed argument function exits then its value will be set in this promise object, so eventually return value will be available in std::future object.

#include <string>

#include <chrono>

#include <thread>

#include <future>

using namespace std::chrono;

std::string fetchDataFromDB(std::string recvdData)

{

// Make sure that function takes 5 seconds to complete

std::this_thread::sleep_for(seconds(5));

//Do stuff like creating DB Connection and fetching Data

return "DB_" + recvdData;

}

std::string fetchDataFromFile(std::string recvdData)

{

// Make sure that function takes 5 seconds to complete

std::this_thread::sleep_for(seconds(5));

//Do stuff like fetching Data File

return "File_" + recvdData;

}

int main()

{

std::future<std::string> resultFromDB = std::async(std::launch::async, fetchDataFromDB, "Data");

//Fetch Data from File

std::string fileData = fetchDataFromFile("Data");

//Fetch Data from DB

// Will block till data is available in future<std::string> object.

std::string dbData = resultFromDB.get();

return 0;

}int initiazer(int x)

{

std::cout<<"Inside Thread, X is "<<x<<std::endl;

return x*x;

}

int main()

{

std::future<int> ftr = std::async(std::launch::async, initiazer, 10);

int res = ftr.get();

std::cout<<res<<std::endl;

return 0;

}std::package_task<> is a class template, therefore we need to pass template parameter to packaged_task<> i.e. type of callable function

// Create a packaged_task<> that encapsulated the callback i.e. a function

std::packaged_task<std::string (std::string)> task(getDataFromDB);// Fetch the associated future<> from packaged_task<>

std::future<std::string> result = task.get_future();1. Object creation logic becomes too convoluted

2. Constructor is not descriptive

- Name mandated by name of containing type

- Cannot overload with same sets of arguments with different names

- Can turn into "optional parameter hell"

3. Object creation (non-piecewise, unlike builder) can be outsourced to

- A separate function (Factory Method)

- That may exist in a separate class (Factory)

- Can create hierarchy of factories with Abstract Factory

Where we need factory:

- We want different constructors of a class, cannot overload because they take the same list of arguments.

- We want the name of constructors be different of class name. Impossible in C++, but available in Swift

// this could work, but the name a and b are not readable, the name of constructor is also vague

enum class PointType

{

cartesian,

polar

};

class Point

{

Point(float a, float b, PointType type = PointType::cartesian)

{

if (type == PointType::cartesian)

{

x = a; b = y;

}

else

{

x = a*cos(b);

y = a*sin(b);

}

}

};Better idea, using a Factory

#include <cmath>

class Point

{

// constructor is private

Point(float x, float y) : x(x), y(y){}

public:

float x, y;

friend class PointFactory; // breaks open OCP, or make everything public

};

class PointFactory

{

static Point NewCartesian(float x, float y)

{

return Point{ x,y };

}

static Point NewPolar(float r, float theta)

{

return Point{ r*cos(theta), r*sin(theta) };

}

};Make constructor private, add static member functions that returns instances.

#include <cmath>

class Point

{

int x, y;

Point(int x, int y) : x(x), y(y) {}

public:

static newCartesian(int x, int y){

return Point{x, y};

// or return {x, y};

}

static newPolar(int r, int theta){

return {r*cos(theta), r*sin(theat)};

}

};

int main()

{

auto p = Point::newCartesian(1, 2);

std::cout<<p.x<<p.y<<endl;

}You have a family of product, based on an abstraction, and you can have a family of factory correspondingly, and they can also based on factory abstractions.

struct HotDrink

{

virtual ~HotDrink() = default;

virtual void prepare(int volume) = 0;

};

struct Tea : HotDrink

{

void prepare(int volume) override

{cout << "Take tea bag, boil water, pour " << volume << "ml, add some lemon" << endl;}

};

struct Coffee : HotDrink

{

void prepare(int volume) override

{cout << "Grind some beans, boil water, pour " << volume << "ml, add cream, enjoy!" << endl;}

};Family of factory

struct HotDrinkFactory

{

virtual unique_ptr<HotDrink> make() const = 0;

};

struct CoffeeFactory : HotDrinkFactory

{

unique_ptr<HotDrink> make() const override

{

return make_unique<Coffee>();

}

};

struct TeaFactory : HotDrinkFactory

{

unique_ptr<HotDrink> make() const override {

return make_unique<Tea>();

}

};Create a map of drink factory that has all different factories. Then you can simply get a factory from the map.

class DrinkFactory

{

map<string, unique_ptr<HotDrinkFactory>> hot_factories;

public:

DrinkFactory()

{

hot_factories["coffee"] = make_unique<CoffeeFactory>();

hot_factories["tea"] = make_unique<TeaFactory>();

}

unique_ptr<HotDrink> make_drink(const string& name)

{

auto drink = hot_factories[name]->make();

drink->prepare(200); // oops!

return drink;

}

};

class DrinkWithVolumeFactory

{

map<string, function<unique_ptr<HotDrink>()>> factories;

public:

DrinkWithVolumeFactory()

{

factories["tea"] = [] {

auto tea = make_unique<Tea>();

tea->prepare(200);

return tea;

};

}

unique_ptr<HotDrink> make_drink(const string& name);

};

inline unique_ptr<HotDrink> DrinkWithVolumeFactory::make_drink(const string& name)

{

return factories[name]();

}

In the first class, make the factory class friend breaks the OCP. So what?

Use inner Factory, which basically put the factory class inside the product class.

class Point

{

Point(float x, float y) : x(x), y(y) {}

// inner class, so you dont need to create a friend that breaks

// OCP

class PointFactory

{

PointFactory() {}

public:

static Point NewCartesian(float x, float y)

{

return { x,y };

}

static Point NewPolar(float r, float theta)

{

return{ r*cos(theta), r*sin(theta) };

}

};

public:

float x, y;

static PointFactory Factory;

};

int main(){

auto pp = Point::Factory.NewCartesian(2, 3);

return 0;

}When it's easier to copy an existing object than fully initialize a new one.

- Complicated objects (cars, iPhone) aren't designed from scratch

- An existing (partially or fully constructed) design is a Prototype

- We make a copy of the prototype and customized it

- Require deep copy support

- Make the cloning convenient

Summary

- To implement a prototype, partially construct an object and store it somewhere

- Clone the prototype ****

- Implement your own deep copy function, or

- Serialize and deserialize

- Customize the resulting instance

The "injection" refers to the passing of a dependency (a service) into the object (a client) that would use it.

Dependency Injection solves problems such as:[3]

- How can an application or class be independent of how its objects are created**?

- How can the way objects are created be specified in separate configuration files?

- How can an application support different configurations?

Creating objects directly within the class that requires the objects is inflexible because it commits the class to particular objects and makes it impossible to change the instantiation later independently from (without having to change) the class. It stops the class from being reusable if other objects are required, and it makes the class hard to test because real objects can't be replaced with mock objects.

A class is no longer responsible for creating the objects it requires, and it doesn't have to delegate instantiation to a factory object as in the Abstract Factory [4] design pattern.

Let's say if you want to write Research code on a database. Then you shouldn't create an instance of that database in the research class, instead, you should inject an instance of the database (take the abstraction as argument and pass any subclass object). Your research (service code) should not depend on how the object is created. When you leave the argument as the abstraction class, that way your code also satisfy that the service code is only depend on abstractions.

- For some components it only makes sense to have one in the system

- Database repository

- Object factory

- The constructor call is expensive

- We only do it once

- WE provide everyone with the same instance

- Want to prevent anyone creating additional copies

- Need to take care of lazy instantiation and thread safety

class Database

{

public:

virtual int get_population(const std::string& name) = 0;

};

class SingletonDatabase : public Database

{

SingletonDatabase(){}

std::map<std::string, int> capitals;

public:

//static int instance_count;

SingletonDatabase(SingletonDatabase const&) = delete;

void operator=(SingletonDatabase const&) = delete;

static SingletonDatabase& get()

{

static SingletonDatabase db;

return db;

}

int get_population(const std::string& name) override

{

return capitals[name];

}

};

class DummyDatabase : public Database

{

std::map<std::string, int> capitals;

public:

DummyDatabase(){}

int get_population(const std::string& name) override {

return capitals[name];

}

};

// service / research code

struct ConfigurableRecordFinder

{

explicit ConfigurableRecordFinder(Database& db)

: db{db}{}

int total_population(std::vector<std::string> names) const

{

int result = 0;

for (auto& name : names)

result += db.get_population(name);

return result;

}

Database& db;

};Multiton pattern allows for the controlled creation of multiple instances, which it manages through the use of a map.

Just use this template:

#include <map>

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

// using enum class for counting the instances

enum class Importance

{

primary,

secondary,

tertiary

};

template <typename T, typename Key = std::string>

class Multiton

{

public:

static shared_ptr<T> get(const Key& key)

{

if (const auto it = instances.find(key);

it != instances.end())

{

return it->second;

}

auto instance = make_shared<T>();

instances[key] = instance;

return instance;

}

protected:

Multiton() = default;

virtual ~Multiton() = default;

private:

static map<Key, shared_ptr<T>> instances;

};

template <typename T, typename Key>

map<Key, shared_ptr<T>> Multiton<T, Key>::instances;

class Printer

{

public:

Printer()

{

++Printer::totalInstanceCount;

cout << "A total of " <<

Printer::totalInstanceCount <<

" instances created so far\n";

}

private:

static int totalInstanceCount;

};

int Printer::totalInstanceCount = 0;

int main()

{

typedef Multiton<Printer, Importance> mt;

auto main = mt::get(Importance::primary);

auto aux = mt::get(Importance::secondary);

auto aux2 = mt::get(Importance::secondary);

}struct foo

{

int x;

int y;

int z;

friend ostream &operator<<(ostream &os, const foo& f){

os << f.x << " " << f.y << " " << f.z <<endl;

return os;

}

};

int main(){

foo a{1, 2};

cout<<a<<endl;

}

/***

1 2 0

/Getting the interface you want from the interface you have.

If you have a function for drawing points, now you want to draw line. What you need is a line to point adapter, take a line and convert to a bunch of points, and then draw the line using the draw_points functions instead of writing a draw_lines function.

Connecting components together through abstractions.

- Bridge prevents complexity explosion

- Example

- Base class threadScheduler

- Can be preemptive or cooperative

- Can run on Windows or Unix

- End up with 2x2 scenario: combination

- Bridge pattern avoids the entity explosion.

When changes are made to a header file, all sources including it needs to be recompiled. In large projects and libraries, it can cause build time issues due to the fact that even when a small change to the implementation is made everyone has to wait sometime until they compile their code. One way to solve this problem is by using the PImpl Idiom, which hides the implementation in the headers and includes an interface file which compiles instantly.

Using Opaque pointer:

Let’s say we are working on an app to deal with images. We want to develop apps for windows, android and apple platforms. We can have shared code which would be used by all platforms and then different end-point can have platform specific code. To deal with images, we have a CImage class exposing APIs to deal with various image operations (scale, rotate, move, save etc). Since all the platforms will be providing same operations, we would define this class in a header file. But the way an image is handled might differ across platforms.

As it can be seen from the above example, while defining blueprint of the CImage class we are only mentioning that there is a SImageInfo data structure.

-

Image.h : A header file to store class declaration. Shared header.

class CImage { public: CImage(); ~CImage(); // opaque pointer // this class depends on the implementation class SImageInfo; SImageInfo* pImageInfo; // we cant see the contents of the class here void Rotate(double angle); void Scale(double factorX, factorY); void Move(int toX, int toY); };

-

Image.cpp : Code that will be shared across different end-points

CImage::CImage() : pImageInfo(new SImageINfo) {} CImage::~CImage() {delete pImageInfo;}

-

Image_windows.cpp : Code specific to Windows will reside here

class CImage::SImageInfo

{ // Windows specific DataSet string get_format() {} };

void CImage::Rotate() { // Make use of windows specific SImageInfo string format = pImageInfo->get_format(); cout<<format<<endl; }

- **Image_apple.cpp :** Code specific to Apple will reside here

~~~c++

class CImage::SImageInfo

{

// Apple specific DataSet

};

void CImage::Rotate()

{

// Make use of apple specific SImageInfo

}

The customers don't need to compile the header files. We can change the implementation whatever we want and give them binary file. The customers can keep use their own header file.

#pragma once

#include <string>

struct Person

{

std::string name;

class PersonImpl;

PersonImpl *impl; // bridge - not necessarily inner class, can vary

Person();

~Person();

void greet();

};#include "Person.h"

struct Person::PersonImpl

{

void greet(Person* p);

};

void Person::PersonImpl::greet(Person* p)

{

printf("hello %s", p->name.c_str());

}

Person::Person()

: impl(new PersonImpl)

{

}

Person::~Person()

{

delete impl;

}

void Person::greet()

{

impl->greet(this);

}A mechanism for treating individual (scale) objects (all kinds of subclasses) and compositions of objects (objects contains other objects) in a uniform manner.

The object and collection of objects (composition) all subclass from abstraction and they all behave the same way.

#pragma once

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <memory>

struct GraphicObject

{

virtual void draw() = 0;

};

struct Circle : GraphicObject

{

void draw() override

{

std::cout << "Circle" << std::endl;

}

};

struct Group : GraphicObject

{

std::string name;

std::vector<GraphicObject*> objects;

explicit Group(const std::string& name)

: name{name}{}

void draw() override

{

std::cout << "Group " << name.c_str() << " contains:" << std::endl;

for (auto&& o : objects)

o->draw();

}

};

inline void graphics()

{

Group root("root");

Circle c1, c2;

root.objects.push_back(&c1);

Group subgroup("sub");

subgroup.objects.push_back(&c2);

root.objects.push_back(&subgroup);

root.draw();

}Class B and Class C are all subclass of A, now when you create a subclass D that inherit from both B and C, then you have two copies of A, which member of A would you actually call? This is an ambiguity.

The solution is to class B: virtual public A{}

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

class A {

public:

int a;

A() // constructor

{

a = 10;

}

};

class B : public virtual A {

};

class C : virtual public A {

};

class D : public B, public C {

};

int main()

{

D object; // object creation of class d

cout << "a = " << object.a << endl;

return 0;

} Virtual class is a nested inner class whose functions and member variables can be overridden or redefined by subclasses of an outer class.

class Machine

{

public:

void run() {}

class parts{

public:

virtual int fun1() = 0;

};

};

class Car::Machine

{

public:

void run(){}